The Bank of England will have to keep interest rates high for longer because inflation will not fade as quickly as it blew up despite recent drops in gas and producer prices, Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent said.

The key question for policymakers is how quickly declining import costs will feed through to domestic price-setting behavior, he said. His conclusion was that it will not be fast, potentially taking longer than the 18 months to two years it took to get embedded.

“It’s unlikely that these second-round effects will unwind as rapidly as they emerged,” Broadbent said at the Federal Reserve’s annual gathering of central bankers in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “As such, monetary policy may well have to remain in restrictive territory for some time yet.”

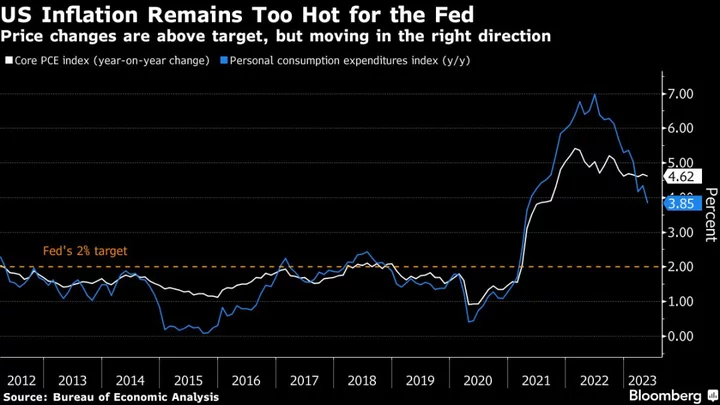

The BOE has raised rates 14 times in a row to 5.25%, the highest level in almost 16 years, to tame inflation. The rate of consumer price growth has dropped from an 11.1% peak to 6.8%, but is still more than three times the 2% target. Markets expect at least two more quarter-point rate increases before the BOE declares success.

In a lengthy speech, Broadbent also argued that governments should bear some of the blame for inflation by being so dependent on a “single source” for gas, from Russia. He added that headline inflation will fall “over the next few months” and UK living standards will start to improve.

His comments followed speeches at Jackson Hole on Friday from European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde and US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, both of whom also signaled that the fight against inflation was not yet won.

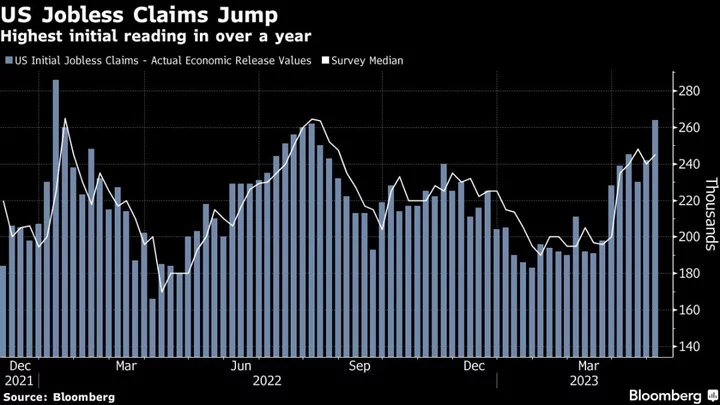

Concerns are mounting that aggressive rate rises since the start of last year risk plunging advanced economies into recession, but central bankers at the Fed’s annual symposium made it clear the rate of inflation remains too high. In a panel discussion following the speech, Broadbent acknowledged the policy risks.

“There’s a risk that we’ve underdone this and may have to do more. But there’s also a risk that we’ve done too much already,” he said.

Inflation Easing

In his speech, Broadbent set out to explain how an imported cost shock got embedded into the UK’s domestic price-setting mechanisms. The original cause was a steep drop in national income caused by external events at a time of tight labor markets, he said, adding that Brexit probably added to labor-market difficulties.

The terms-of-trade hit “has been greater even than in other countries in Europe” as well as the US due to the openness of the UK economy, he said. In the two years to the third quarter of 2022, Broadbent estimated that rising import costs “knocked close to 6% off real national income.”

Both workers and businesses then competed to recover those losses by demanding wage increases and raising selling prices, he said.

“The good news is that these import prices have now been subsiding for a while,” he said, noting that wholesale European gas prices had fallen since peaking almost a year ago, and manufacturing output prices have also declined.

“We can expect this to feed through to retail-goods inflation over the next few months,” he said. “In time, it’s also likely to relieve pressure on real incomes and, for that reason, on domestic rates of inflation.”

But it will likely take longer for those factors to unwind than it did for them to emerge,” he added.

Russian Gas

Governments should learn from the inflation shock not to let trade get over-concentrated in the future, as they did with Russian gas, Broadbent also said.

“The argument that governments have a role to play in addressing the problem is surely reasonable when it comes to Europe’s pre-war reliance on Russian gas,” he said. “Arguably security of energy supply is something for which governments should and do take some responsibility. There’s nothing intrinsically special about Russian gas in particular: one molecule of methane is much like another.”

Similarly, he said there “may be good political reasons – political imperatives, even – to repatriate production in some strategic areas.” But one common conclusion following the pandemic — that global supply chains are fragile – was wron; they “have actually proved relatively robust,” Broadbent said.

(Updates with comment from Broadbent in eighth paragraph.)