Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt will provide a £21 billion ($26.2 billion) stimulus to the UK economy in the run-up to the next election, threatening to fuel inflation and prompt the Bank of England to keep interest rates in painfully high territory.

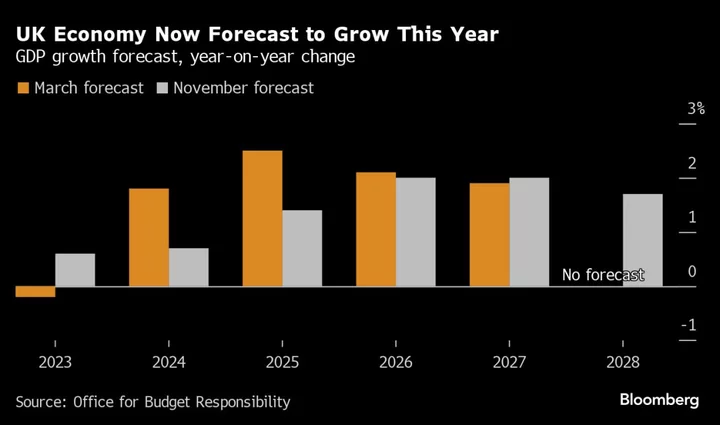

The Office for Budget Responsibility said the measures set out by Hunt on Wednesday will boost the economy by an average of just under 0.3% between the fiscal years ending March 2025 and 2029. The fiscal watchdog also has a more pessimistic outlook for inflation and for the UK economy’s potential growth rate than it did in March.

The stimulus — which included a cut to levies that workers pay to fund national insurance — leaves the Chancellor open to accusations that he reneged on a promise to avoid tax cuts that stoked inflation. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has put cutting inflation at the top of his agenda and is concerned that soaring borrowing costs are hurting households.

“That may mean the Bank of England is less inclined to cut interest rates in the middle of next year and may hold off until late in 2024, as we expect,” said Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics. He said slightly faster growth next year means inflation will be will be “a little higher than otherwise.”

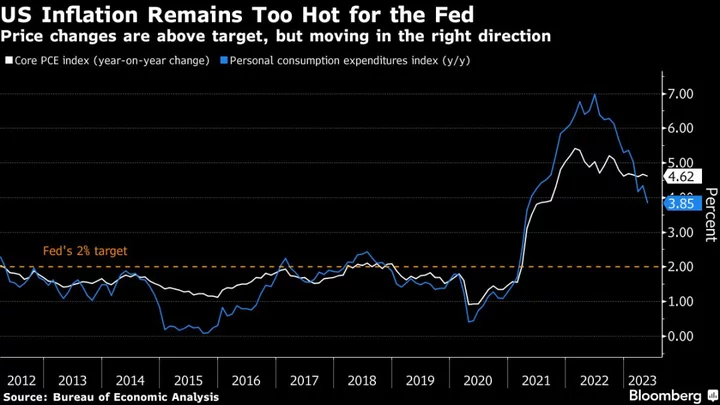

Documents released alongside Hunt’s Autumn Statement showed the package will provide a £6.7 billion stimulus in 2023-24 and a £14.3 billion boost next year. The Treasury is loosening the purse strings at the moment the BOE is working to bring inflation down to its 2% target from 4.6% currently.

Economists said the package could provide a small lift to inflation, which may underpin the case for keeping rates at the highest level since 2008. While markets are pricing in interest rate cuts in mid-2024, BOE Governor Andrew Bailey has said it is far too early to consider reductions given the upside risks to inflation.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, said the ambition to cut taxes is “virtuous but impractical at a time when debt is still rising and inflation is well over 2%.”

The OBR warned inflation will be much stronger than it expected in the spring, slowing from 7.5% in 2023 to 3.6% in 2024. Next year’s forecast is almost 3 percentage points higher than its previous projection.

The impact of the measures on inflation could be only modest. The OBR estimated that demand fed by the Treasury’s package will outstrip supply by 0.1% in 2025/26, the peak of the effect.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“For the UK economy, the policy package is likely to deliver a modest boost though not enough to move the needle on the inflation outlook. We remain more downbeat than the fiscal watchdog’s new projections over the coming year and beyond.”

—Dan Hanson, Bloomberg Economics. Click for the INSIGHT.

Some economists think Hunt’s package won’t be a problem for inflation or the BOE. Parts of the Autumn Statement are aimed at lifting the supply side of the economy with incentives for businesses to invest and reforms to increase worker participation. Those will dampen the threat to inflation.

The package in total will “mitigate the risk that tax cuts will boost demand and prove inflationary,” said Thomas Pugh, economist at RSM UK. “Most of the reason the Chancellor has been able to cut taxes is because he has kept departmental spending steady, meaning a real terms reduction to spending to fund tax cuts. This limits the aggregate impact on demand and inflation.”

Even with Hunt’s efforts to boost supply, the OBR gave a gloomier assessment on the UK economy’s prospects.

It downgraded its forecast for medium term potential output growth by 0.1 percentage points to 1.6%, meaning the economy can grow less quickly before demand stokes inflation. That is still far more optimistic than the BOE’s prognosis.

The OBR’s projections showed a flatlining economy in the coming years with growth slowing to 0.6% in 2023. Growth under its estimates will remain lackluster at 0.7% in 2024 before picking up to 1.4% in 2025.

“The Chancellor has delivered an Autumn Statement that rightly focuses on tackling the UK’s main economic problem, stagnant long-term growth,” said Christopher Breen, head of economic insight at the Centre for Economics and Business Research. “The only way to sustainably do so is to improve the productive capacity of the economy.”