Italy may slow down its deficit-reduction plans after the economy unexpectedly shrank, a move that would give the government leeway to continue spending on campaign promises such as more tax cuts.

This means Italy may not meet its deficit forecasts of 4.5% of gross domestic product this year and 3.7% in 2024, according to people familiar with the issue who spoke on condition of anonymity because discussions are ongoing.

The matter has not yet been discussed at ministerial level, the people said. The Finance Ministry when contacted said it doesn’t comment on speculation.

Finance Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti said at an event in Rimini, Italy on Monday that the new budget law “will be complicated” and that the government “wont be able to do everything.”

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni promised tax cuts for lower-income families, as well as a general rationalization and reduction of levies in Italy’s byzantine tax system. She also vowed to continue helping households struggling with energy prices, and maintain current retirement norms and some other welfare benefits.

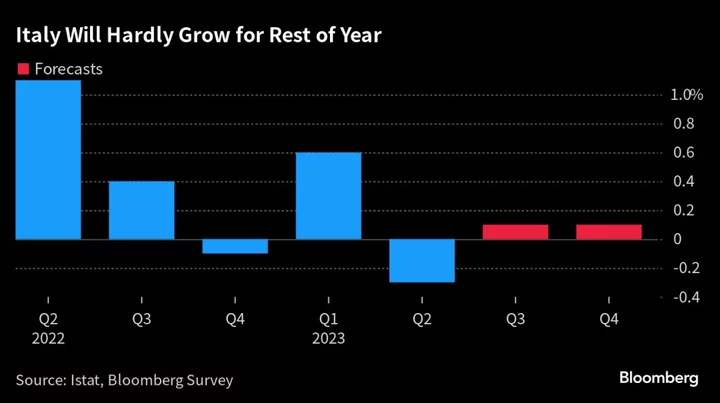

Giorgetti had hoped Italy’s good economic performance last year and in the first quarter of 2023 meant it could grow out of its financial difficulties, but an unexpected 0.3% contraction in the second quarter has made targets more difficult to achieve.

The economy expanded by 0.6% in the first three months of the year, but rising interest rates, weakening global export demand and economic difficulties in key trading partners such as Germany are starting to take their toll. Italian output in the remainder of 2023 doesn’t look strong either, with economists predicting just 0.1% increases in the next quarters.

Fiscal Leeway

With the European Union’s fiscal rules suspended since the pandemic, the government does have some leeway, however. The bloc aims to agree on a reform of the so-called Stability and Growth Pact by the end of this year, and is trying to reconcile differences between a group of countries led by Germany that want strict limits on spending, and Italy, France and others that worry pressure to reduce debt quickly could hinder growth and investment.

The suspension ends at the start of 2024.

Giorgetti said he hoped the old pact — which set a 3% deficit limit that has been kept in the EU Commission’s new legislative proposals — would not be reinstated without changes.

“It’s not an issue of debt or of lack of debt reduction for us,” he said, adding that Italy wants special consideration to be given to investments aimed at growth.

There is no doubt that Italy will continue to reduce its debt, the people familiar with the matter said. The tweaks to the deficit forecasts would be small and the overall trajectory would continue to show a reduction, they added.

The Bank of Italy is due to publish the country’s current account balance as of June on Tuesday.

So far, Meloni has kept the nation’s mammoth debt on a declining path and her first budget law was moderate and devoid of excessive spending or norms that could upset markets or the country’s European partners. That has kept the spread between Italian 10-year bonds and German counterparts well-below 200 basis points for most of her premiership.

The need to rustle up cash in an increasingly difficult economic environment may complicate things, however, with the government shocking markets earlier this month after passing a surprise 40% windfall tax on banks’ profits. The levy was both a nod to Meloni’s populist base and a way to find funds without resorting to more state borrowing.

The norm may yet be watered down in parliament, which means it may generate less than the expected €2 billion to €3 billion ($2.2 billion to $3.3 billion). That means money to pay for welfare and tax cuts will have to be found elsewhere.

(Updates with timing of current account balance data in 13th paragraph.)