The yen is close to hitting a bottom against the dollar, and is unlikely to weaken to levels requiring Japan’s intervention, analysts said.

The currency has declined more than 6% this year, touching 140.23 on Thursday. It’ll probably bottom out at around 142-143 yen, with an improving trade account and higher tourism arrivals offering support, according to Market Risk Advisory.

Japan spent ¥9.1 trillion yen ($65 billion) last year to support its currency through multiple interventions after it first hit 145.90 against the dollar. Selling the yen was a favorite macro strategy with hedge funds in 2022 as the US aggressively raised interest rates while the Bank of Japan maintained its ultra-loose monetary policy.

“The situation is different from last year, especially as the deficit now is much smaller, with the recovery of inbound tourism and trade account limiting the yen’s downside,” said Koji Fukaya, a fellow at Market Risk Advisory. There aren’t enough factors to send the yen beyond 145 and close to the 150 area, he said.

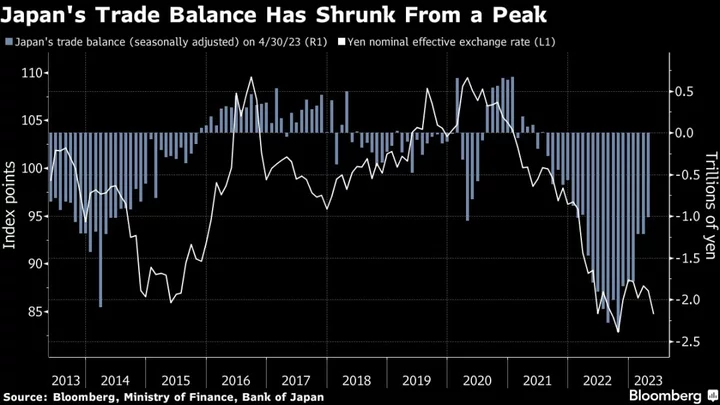

While there’s still a wide rates differential with the US, Japan’s economic situation is improving. The trade deficit has narrowed from a record high of ¥2.4 trillion in October, on a seasonally adjusted basis, to a trillion yen, according to Ministry of Finance data. More than 1.9 million foreigners visited in April, around two-thirds of pre-Covid levels, and further recovery is expected by economists.

Global funds are also starting to pile into Japanese equities, supporting the yen, with the benchmark Topix Index hitting a 33-year high last week. Non-resident investors were net buyers for eight straight weeks, purchasing more than ¥7 trillion during the period through May 19, according to official data.

And unlike last year when yen weakness drew warnings from the authorities, there has been little commentary from officials. Then, the government conducted interventions three times, with the currency weakening to as low as 151.95, a level not seen since 1990, in October.

“We don’t even see verbal intervention these days as 140 is not as alarming as it was last year, and also because the Japanese equities market has performed very well thanks to the weaker yen,” said Daisaku Ueno, chief currency strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities in Tokyo. “In addition, crude oil prices have dropped and fears about inflation stemming both from the weaker yen and higher imported prices have eased,” he said.

Leveraged funds have started cutting short positions on the yen, with the number of contracts held against it dropping to 42,720 for the week endedg May 16, from 50,283 in March. They had soared to almost 72,000 contracts last year.

Their shifting bets may reflect expectations for the Federal Reserve to pivot. Traders are pricing in peak rates to be reached in the next two policy meetings, followed by a cut in December. Meanwhile, new BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has stressed a desire for policy flexibility, unlike his predecessor. In his latest interview, Ueda said he hadn’t ruled out policy changes even if inflation is below a targeted 2%.

“The yen may consolidate around here first and it may take some time to see a further decline toward the 142 area,” said Jun Kato, chief market analyst at Shinkin Asset Management Co. “Intervention is less effective when the position is not one way and the move is gradual, so from such a technical perspective, it is unlikely.”

--With assistance from Ruth Carson and Masaki Kondo.