DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — The United States and Iran reached a tentative agreement this week that will eventually see five detained Americans in Iran and an unknown number Iranians imprisoned in the U.S. released from custody after billions of dollars in frozen Iranian assets are transferred from banks in South Korea to Qatar.

The complex deal — which came together after months of indirect negotiations between U.S. and Iranian officials — was announced on Thursday when Iran moved four of the five Americans from prison to house arrest. The fifth American had already been under house arrest.

Details of the money transfer, the timing of its completion and the ultimate release of both the American and Iranian prisoners remain unclear. However, U.S. and Iranian officials say they believe the agreement could be complete by mid- to late-September.

A look at what is known about the deal.

WHAT’S IN IT?

Under the tentative agreement, the U.S. has given its blessing to South Korea to convert frozen Iranian assets held there from the South Korean currency, the won, to euros.

That money then would be sent to Qatar, a small, energy-rich nation on the Arabian Peninsula that has been a mediator in the talks. The amount from Seoul could be anywhere from $6 billion to $7 billion, depending on exchange rates. The cash represents money South Korea owed Iran — but had not yet paid — for oil purchased before the Trump administration imposed sanctions on such transactions in 2019.

The U.S. maintains that, once in Qatar, the money will be held in restricted accounts and will only be able to be used for humanitarian goods, such as medicine and food. Those transactions are currently allowed under American sanctions targeting the Islamic Republic over its advancing nuclear program.

Some in Iran have disputed the U.S. claim, saying that Tehran will have total control over the funds. Qatar has not commented publicly on how it will monitor the disbursement of the money.

In exchange, Iran is to release the five Iranian-Americans held as prisoners in the country. Currently, they are under guard at a hotel in Tehran, according to a U.S.-based lawyer advocating for one of them.

WHY WILL IT TAKE SO LONG?

Iran does not want the frozen assets in South Korean won, which is less convertible than euros or U.S. dollars. U.S. officials say that while South Korea is on board with the transfer it is concerned that converting $6 or $7 billion in won into other currencies at once will adversely affect its exchange rate and economy.

Thus, South Korea is proceeding slowly, converting smaller amounts of the frozen assets for the eventual transfer to the central bank in Qatar. In addition, as the money is transferred, it has to avoid touching the U.S. financial system where it could become subject to American sanctions. So a complicated and time-consuming series of transfers through third-country banks has been arranged.

WHO ARE THE DETAINED IRANIAN-AMERICANS?

The identities of three of the five prisoners have been made public. It remains unclear who the other two are. The American government has described them as wanting to keep their identities private and Iran has not named them either.

The three known are Siamak Namazi, who was detained in 2015 and later sentenced to 10 years in prison on internationally criticized spying charges. Another is Emad Sharghi, a venture capitalist serving a 10-year sentence.

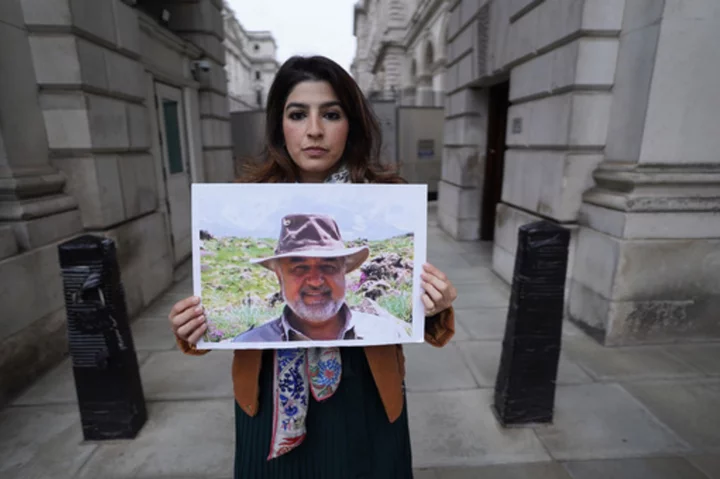

The third is Morad Tahbaz, a British-American conservationist of Iranian descent who was arrested in 2018 and also received a 10-year sentence.

Those advocating for their release describe them as wrongfully detained and innocent. Iran has used prisoners with Western ties as bargaining chips in negotiations since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

WHY IS THIS DEAL HAPPENING NOW?

For Iran, years of American sanctions following former U.S. President Donald Trump's withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal with world powers has crushed its already-anemic economy.

Previous claims of progress in talks over the frozen assets have provided only short-term boosts to Iran’s hobbled rial currency.

The release of that money, even if only disbursed under strict circumstances, could provide an economic boost.

For the U.S., the administration of President Joe Biden has tried to get Iran back into the deal, which fell apart after Trump's 2018 withdrawal. Last year, countries involved in the initial agreement offered Tehran what was described as their last, best roadmap to restore the accord. Iran did not accept it.

Still, Iran hawks in Congress and outside critics of the 2015 nuclear deal have criticized the new arrangement. Former Vice President Mike Pence and the ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Sen. Jim Risch, as well as former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, have all compared the money transfer to paying a ransom and said the Biden administration is encouraging Iran to continue taking prisoners.

WILL THE U.S. RELEASE IRANIAN PRISONERS HELD IN AMERICA?

On Friday, Iran’s Foreign Ministry made a point of bringing up those prisoners. American officials have declined to comment on who or how many Iranian prisoners might be released in a final agreement. But Iranian media in the past identified several prisoners with cases tied to violations of U.S. export laws and restrictions on doing business with Iran.

Those alleged violations include the transfer of money through Venezuela and sales of dual-use equipment that the U.S. says could be used in Iran’s military and nuclear programs.

DOES THIS MEAN IRAN-U.S. TENSIONS ARE EASING?

No. Outside of the tensions over the nuclear deal and Iran's atomic ambitions, a series of attacks and ship seizures in the Mideast have been attributed to Tehran since 2019.

The Pentagon is considering a plan to put U.S. troops on board to guard commercial ships in the Strait of Hormuz, through which 20% of all oil shipments pass moving out of the Persian Gulf.

A major deployment of U.S. sailors and Marines, alongside F-35s, F-16s and other aircraft, is also underway in the region. Meanwhile, Iran supplies Russia with the bomb-carrying drones Moscow uses to target sites in Ukraine amid its war on Kyiv.

___

Lee reported from Washington.