All of a sudden, the biggest interest-rate shock in decades is rousing traders from their slumber once again with soft echoes of 2022’s everything-selloff.

More than a year after central bankers began their most forceful monetary tightening in decades, money managers just got blindsided by the latest signs that the world’s biggest economy continues to run hot. Cue a renewed in-tandem plunge in stocks and bonds like the bad days of 2022.

After strong labor data from the ADP Research Institute fueled fresh bets that the Federal Reserve would need to ramp up its monetary medicine, two-year Treasury yields spiked Thursday to levels last seen in 2007 and the 10-year rate jumped above 4%, retesting last year’s highs. Earlier, traders in the UK unleashed wagers that the benchmark rate would peak to levels last seen in 1998 at 6.5%, in the aftermath of Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey’s warning that inflation is still “far too high.”

While the better-than-expected economic data in the US has dispelled fears that a recession is imminent, the trading action suggests Wall Street has yet to make peace with higher rates for longer.

Just ask Scott Bauer. When the ADP data dropped, the chief executive officer at Prosper Trading Academy had to stop his gym workout in Colorado to rush back to his desk.

“When that number hit, I took a good second and third look at my positions just to make sure that everything was going to be OK,” said Bauer, who leads a firm that coaches clients on trading stocks and options. “This one really, I mean really, is out of the box.”

After ignoring the steadily higher yields for the past few months, the stock market peace is beginning to fray. The Cboe Volatility Index, the so-called fear gauge measuring expected equity price swings, surged at one point the most since the regional bank turmoil in March.

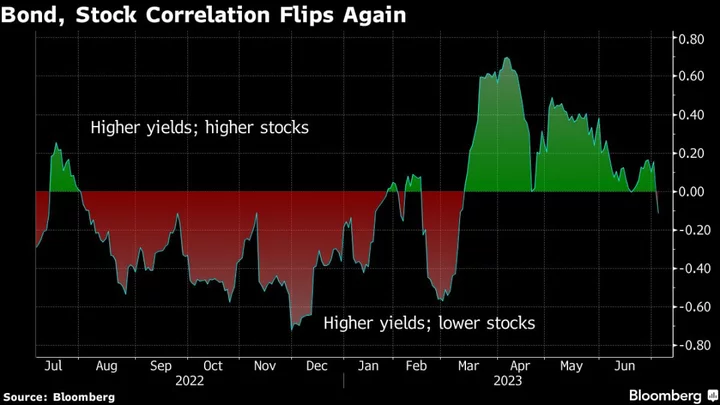

To cap it off, the one-month correlation between 10-year yields and the S&P 500 has flipped to negative for the first time in three months — meaning that both Treasuries and shares have tended to sell off all at once. If this inflation-era trading pattern endures, it spells bad news for just about everyone but especially the trillion-dollar 60/40 complex and so-called risk-parity quants.

“The problem is that for whatever reason, the economy isn’t slowing down fast enough,” said Harry Melandri, a consultant to Macro Intelligence 2 Partners, whose clients include hedge funds. “The Fed looks like it has more to do. And if so, a lot of the market is a little bit offside. I don’t think positions are huge, but they are not positioned for more hikes.”

The renewed market tension underscores the uneasiness among investors that policymakers have to keep lifting borrowing costs to curb inflation, at the risk of sending the economy into a tailspin. Yield curves from the US to Germany are mired in deep inversions, which historically have presaged recessions.

Still, choppy markets this week pale in comparison to the volatility witnessed last year, marked by double-digit losses across assets and a collapse in confidence in hedging strategies. The S&P’s 1% loss over the past two days came after posting gains in six of the past seven weeks and the major benchmarks have unexpectedly posted big rallies this year, all largely thanks to AI euphoria.

In the credit market, the spread between junk bonds and Treasuries remains near the lows for the year, a sign that distress has yet to hit the broader marketplace.

But it’s the shift in Wall Street’s reaction to data this week that has stirred concerns among some investors. That stocks fell in reaction to strong economic news marks a break from their behavior as recently as last week — when strong readings on consumer confidence, new home sales, jobless claims and gross domestic product were the impetus for rallies.

Underpinning the shift is a recalibration of bets on the Fed’s hiking campaign. On Thursday, Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan said more interest-rate increases will likely be needed to spur meaningful disinflation, echoing the tone in the minutes of the June meeting. The rate markets have penciled in one more hike for July, but remain split over whether monetary officials will deliver another, as the Fed’s so-called dot plot shows.

The more the Fed raise rates, the deeper the recession might be, which will lead to lower rates eventually, according to Subadra Rajappa, head of US interest rates strategist at Societe Generale SA. She’s recommending clients bet on a steeper curve, whereby short-term rates could fall relative to longer-term yields. But she acknowledged that it’s not an easy trade to hold thanks to the market volatility.

“It’s a frustrating environment for investors on either side of the trade, unfortunately,” said Rajappa.

--With assistance from Lu Wang and Emily Graffeo.