Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has left the door open to another interest-rate hike, but Wall Street economists see the signs pointing in one direction ahead of the central bank’s September meeting: pause.

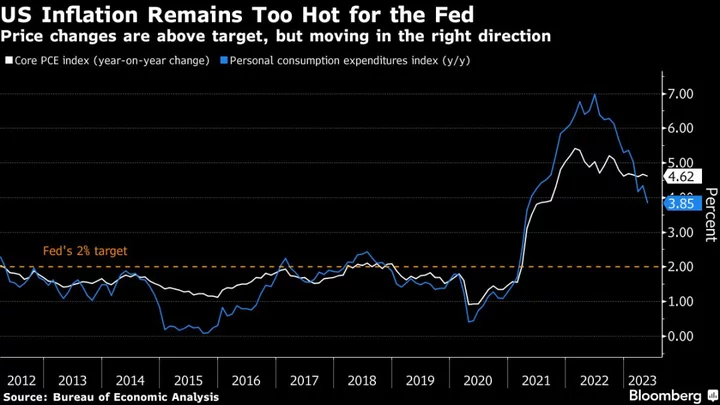

Policymakers in recent days have said they’re waiting on incoming data to guide their decision on whether to raise rates at the Fed’s next gathering. The latest surprisingly mild inflation reports, signs of moderating consumer spending and evidence of diminishing wage pressures have suggested there’s little urgency to raise rates next month.

Further tame inflation readings expected before the Fed’s Sept. 19-20 meeting, as well as looming headwinds including the resumption of student-loan payments, will give them more reason to hold off, even if temporarily, economists say. Markets were pricing in about one in five odds of a hike in September.

“I suspect the data will be mild enough to meet with the Fed’s approval,” said Douglas Porter, chief economist at Bank of Montreal. “Our core view is that the Fed has done enough, with short-term rates now solidly in positive real terrain, core inflation beginning to come down, and the labor market softening around the edges.”

Consumer prices excluding food and energy are likely to rise just 0.2% in July and August, estimates Omair Sharif, president and founder of Inflation Insights, who dubs this the “summer of disinflation.” Those low readings would follow better-than-expected prints on the Fed’s preferred measure for June, which Friday showed the inflation rate dropping to a two-year low of 3%.

The Federal Open Market Committee raised the rates range Wednesday to a 22-year high of 5.25% to 5.5%. Powell said the September meeting would be “live” for a possible further hike, depending “on the totality of incoming data and their implications for the outlook.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“Softer wage growth — the one aspect of the economy that had been slow to cool so far — assures Fed officials that the labor market is easing, and was something Fed Chair Jerome Powell described as a necessary condition for continued progress on disinflation. This print — along with a separate report that showed core PCE inflation growing at a pace consistent with the Fed’s 2% target — strengthens our view that the FOMC will hold rates steady at the September meeting.”

— Anna Wong, chief US economist

To read the full note, click here

There’s considerable evidence that core inflation, excluding food and energy, is coming down. Used car prices, an important swing factor, decreased in the first 15 days of July, according to Manheim Auctions, the world’s largest reseller of used vehicles. Apartment rent prices in the US have edged lower from August 2022, according to rent.com’s research.

The latest evidence of softening came with Monday’s release of the Fed’s senior loan officer survey, which showed continued credit tightening. Policymakers will get fresh data this week on jobs openings and hiring, which economists expect will show some further easing in the labor market.

The Fed has since early last year engaged in the most aggressive tightening campaign since the 1980s in an effort to curb the rate of inflation, which in 2022 hit a 40-year high. While policymakers paused rate hikes in June to assess the impact of previous moves, they also signaled at the time that two more increases would probably be appropriate by the end of the year.

By September, the FOMC is likely to reduce its 2023 estimate for core inflation to 3.6% or 3.7% from 3.9% in June, according to Sharif. With that kind of adjustment, Fed officials who say they are data-dependent might be hard pressed to explain any near-term hike.

Powell has been especially worried about prices in the services sector such as restaurants, hotels and hair salons driven by a tight labor market, but the Fed got good news there Friday as well. The employment cost index, a broad gauge of wages and benefits, increased 1% in the second quarter, marking the slowest advance since 2021, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics figures released Friday.

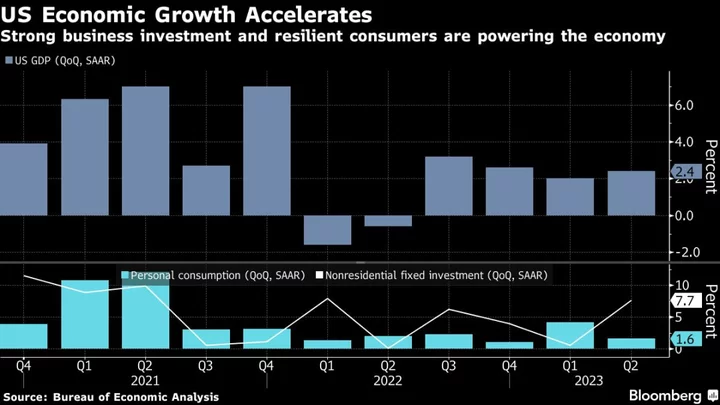

The reports have been consistent with Powell’s view that the economy can slow to a soft landing, in which inflation returns to the 2% target without a recession or serious damage to the labor market. Yet there are threats ahead to the growth outlook that might, on the margin, argue for caution about more short-term hikes.

The Fed could be reluctant ahead of October’s resumption of student-loan payments, which PNC Financial Services Group economists say will average $350 to $400 per month for close to 27 million borrowers and will be modestly negative for consumer spending. The central bank will also monitor the possibility of a government shutdown brought about by a stalemate in Congress, though they could judge the consequences as likely to be short-term.

Even with a September pause, Powell and the FOMC may want to keep their options open for November and December meetings and they will be wary of declaring victory on inflation prematurely.

“The Fed is not basing their actions on forecasts, given they have been wrong before,” said Rubeela Farooqi, chief US economist at High Frequency Economics. “They want confirmation from the data.”

Inflation surprised to the upside during much of 2021 and 2022 and Powell has warned the process of lessening price pressures will be uneven.

“I want to stress, this process of improvement will not be as linear as everyone will want,” said Tom Porcelli, chief US economist at PGIM Fixed Income. “Inflation is starting the process of slowing. That can be bumpy. But the broad trend will be clear by year end.”