SAN DIEGO (AP) — U.S. authorities are sharply expanding the reach of curfews for the heads of asylum-seeking families while they wait for initial screenings after crossing the border, signaling they are comfortable with early results of what is intended as an alternative to detention.

The curfews began in May in four cities and, on Friday, grow to 13 locations, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials told advocates. The additions are Boston, Providence, Rhode Island, and San Diego, San Francisco and San Jose in California. New Orleans and Houston started July 28.

The number of cities is expected to reach 40 by the end of September, according to a U.S. official who was not authorized to discuss the matter publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

The curfews, which run from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. are designed to stay in effect until the outcome of screenings, known as “credible fear” interviews, by asylum officers and any appeal to an immigration judge. Those who pass are generally allowed to pursue their asylum cases in court without a curfew, while those who fail are supposed to be deported.

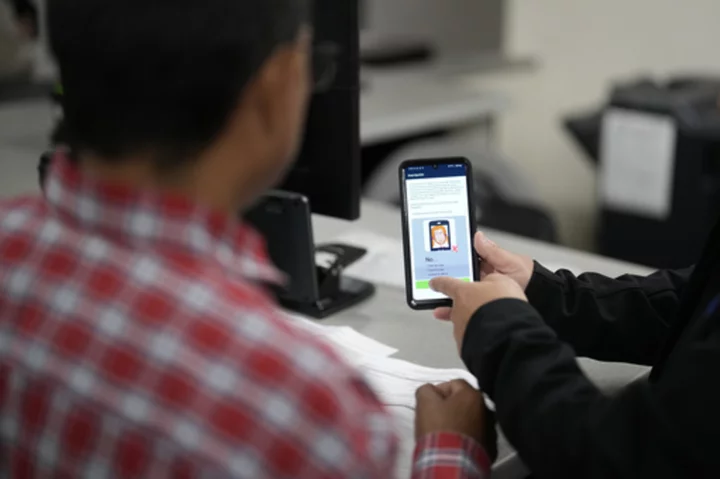

ICE announced the curfews as pandemic-related asylum restrictions expired in May, part of a broader strategy that includes keeping single adults in Border Patrol custody until screenings are complete. Authorities considered reviving family detention but opted for curfews, which apply to heads of household and also require ankle monitors.

The expansion indicates ICE is comfortable with initial results of what it calls the Family Expedited Removal Management program, or FERM, in Baltimore; Chicago; Newark, New Jersey; and Washington. Denver and Minneapolis were added later.

“While FERM initially began in four locations, (the Department of Homeland Security) is quickly expanding to cities across the country and is removing families who are determined to be ineligible for relief and are ordered removed through this non-detained enforcement process,” the agency said in a statement.

ICE told advocates last week that it aimed to have up to 500 families under curfews at any given time, said Cindy Woods, national policy counsel for Americans for Immigrant Justice. There were about 200 families under curfew at the time.

The number of families enrolled is expected to grow significantly as the program expands, the U.S. official said.

Some immigration advocates feel screenings are rushed. Americans for Immigrant Justice said asylum-seekers generally have screenings within 12 days of crossing the border and only a day or two to prepare for an appeal. Those who fail to win approval are expected to be deported within 30 days of arrival.

“Families need to take a breath," Woods said in a conference call last week with other attorneys.

Still, she said, the curfews “are a step in right direction if it's a step away from potential detention of families.”

Jon Feere of the Center for Immigration Studies, a group that advocates for immigration restrictions, said he worried about potential no-shows. “Congress should demand an accounting of all absconding, arrests, and removals so this new program can be evaluated,” he wrote in an email.

Under a court order, the government generally can detain families no more than 20 days. The Obama and Trump administrations detained families, but President Joe Biden ended the practice shortly after taking office in 2021.

It is unclear how effective curfews have been at making sure asylum-seekers show up for screening interviews. Americans for Immigrant Justice said the roughly 30 families it has advised have perfect attendance.

Yaniris, a 30-year-old Honduran woman who spoke on condition that her last name not be published due to safety concerns, said the curfew and ankle monitor was “a thousand times better” than being detained, despite being self-conscious about being seen with the monitoring device.

“I understand that laws are laws and they have to be respected,” she said.

Yaniris spent more than three months traveling with her 2-year-old daughter from Honduras to Eagle Pass, Texas, where she surrendered to Border Patrol agents. She said she had five or six days to prepare for her screening interview, which came after a sleepless night with her sick daughter, and she failed it.

“The problem was that I didn't explain myself well," she said of the screening interview. "I wasn't in control of myself that day.”

Yaniris scrambled to find an attorney before her appeal. One finally called back as she was on her way to the appeal, and she had to cut short the conversation after 20 minutes. The judge agreed to a two-day delay.

On Monday the lawyer called to say she had won on appeal. She is now waiting for a court date in a system backlogged with 1.2 million cases that often take years to resolve.