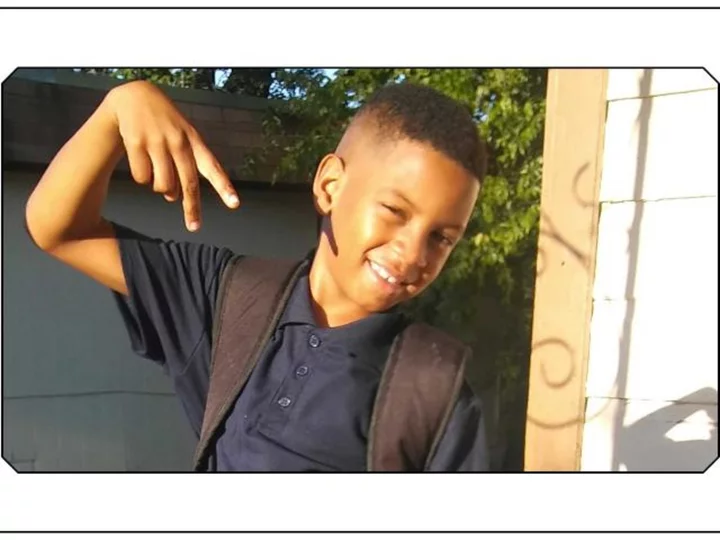

Trey'shawn Eunes was confused.

"Why would you give me Brooklyn's uncle's shirt?" the 11-year-old asked his mother last year, staring at the latest in their family's series of T-shirts personalized to mark special milestones.

This time, it was a baby shower: Trey'shawn's older brother was expecting.

"You are Brooklyn's uncle," his mother, Lakesha Bay, told him, recalling to CNN how her son's eyes lit up and his smile spread as the realization struck.

He threw on the shirt.

Trey, as his mom calls him, was just a kid. But he was going to be an uncle.

A year later came another shirt commemorating Trey's niece's first birthday.

Trey never got to wear it.

Instead, his mom placed it in his casket days after he was fatally shot.

The proud young uncle had been at a gathering in Fort Worth, Texas, with his father on Juneteenth when police believe a 3-year-old picked up a handgun and accidentally fired it, striking Trey as he played video games, according to an arrest warrant for a man accused of tampering with evidence after the shooting.

At just 12, Trey became one of more than 1,300 children and teens in the United States killed by a gun so far in 2023, according to the Gun Violence Archive, as firearms surpassed motor vehicles in 2020 as the No. 1 killer of children and teens in America -- a particularly grim facet of the gun violence epidemic ravaging US communities.

Gun violence is an epidemic in the US. Here are 4 things you can do today

Trey's death also makes Bay one of many mothers struggling with the pain of losing a child to the scourge. She feels the devastating loss anew each morning when she opens her eyes.

"Every day I have to relive that as a parent," Bay told CNN through tears. "A child passing away, he doesn't just pass away one time. He passes away every day. Every morning I wake up, it hits me like I'm getting hit by a car ...

"It's the worst kind of pain for your child to not just have died but to die over and over and over again."

A charismatic young athlete

In the same way Trey doted on his niece -- "He was obsessed with Brooklyn," Bay said -- the family had long doted on him.

When Trey was little, relatives used to argue over who would get to hold him or which sibling would sit with him in the backseat of the car, she said. Trey, in turn, loved his siblings and was close with all of them, Bay said.

"He's always been the family favorite," she said.

That adoration extended well beyond his family. Trey was charismatic; wherever he went, making friends came easy to him, his mom said, whether they were his classmates, teammates or kids in the neighborhood. If he wasn't playing football or PlayStation, you'd find him outside with them, riding his electric scooter.

Trey was a natural athlete, Bay said. She recalled fondly how, several years ago, he had to try out -- not just sign up -- for a football team for the first time. They both knew he would make the roster, but Bay still remembers their shared joy when they saw his name on the list.

"We were just like jumping up and down, hugging each other, taking pictures of his name on the list," she said, calling it one of her "favorite memories."

"He achieved something, and he worked for it, and he actually made the team," Bay said. "I could tell that it did something for him. I was just happy for him."

Read other profiles of children who've died from gun violence

Trey loved playing on that team, his mother said, and he was good at it -- among their best. He was a starter and never taken out of the game.

Trey's love of football was evident too at home, where he often played Madden NFL on his PlayStation 4. He competed online with his best friend, Bay said, but he and his friends each had miniature TVs they would lug back and forth to each other's homes, so they could play together.

'He wanted to make me so proud'

For years, Trey would tell people he wanted to be a police officer when he grew up. But as he got older, he wasn't sure, his mom said. When she asked what he might want to do, he asked her in turn, "What do you think I'd be good at?"

Really, he just wanted to make people proud, especially his mom and dad. But that was easy, Bay said. Trey was a "really good kid," always doing his best in school and never disobedient or troublesome. And though money could be tight, his mom tried to find ways to reward him: a trip to the trampoline park here, a PlayStation gift card there.

"He deserved it," she said.

Just weeks before he died, Trey finished sixth grade and was looking forward to middle school. He was stylish and already was talking with Bay about what clothes and shoes he wanted to get before school started. And he was getting ready to try out for the school football team, one his mother knew he would have made.

But he was most excited because he'd be attending the same middle school his mom had. They dreamed of seeing him follow in her footsteps, eventually graduating from her alma mater, James Martin High School in Arlington, Bay said.

Now, Trey will never get that chance, at least not the way he imagined it. When he finished sixth grade this spring, he and his classmates had a graduation ceremony -- at Martin High School.

"I still look at it this way: He achieved that goal for me, for him. He still graduated at Martin High School," Bay said. "I'll always have that in my heart because that's what he wanted to do.

"He wanted to make me so proud all the time."