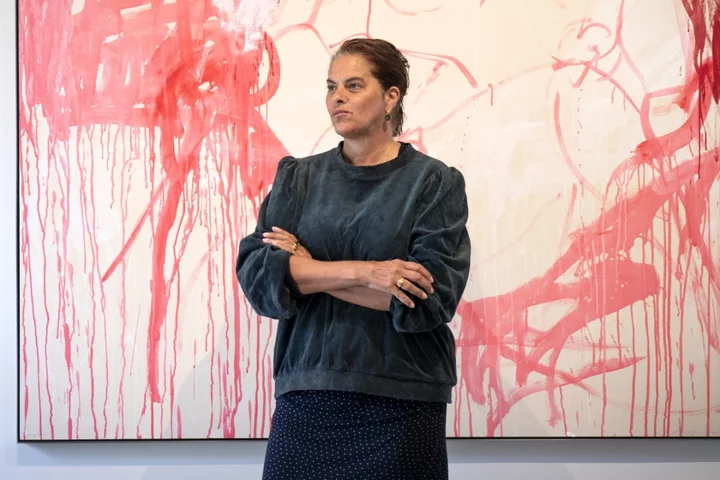

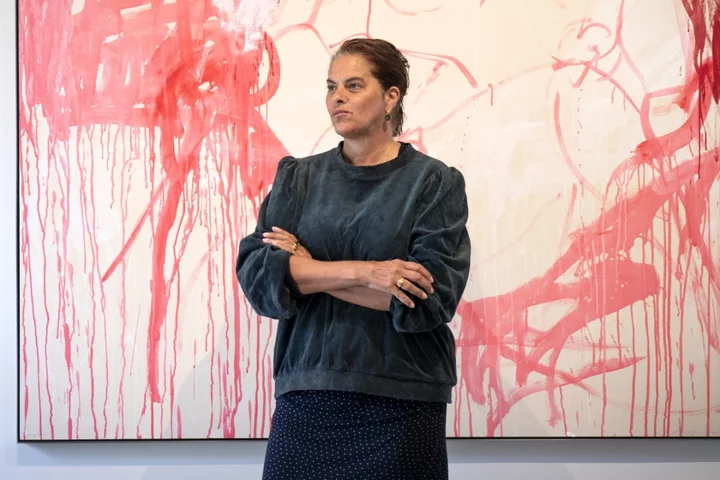

Tracey Emin says she ‘totally accepted death’ following cancer diagnosis: ‘That’s what kept me alive’

Tracey Emin has opened up about “totally accepting death” when she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of bladder cancer in 2020. In June 2020, visual artist Emin was diagnosed with cancer, and subsequently underwent a series of major surgeries, including a full hysterectomy, as well as the removal of her urethra, bladder, lymph nodes, and part of her vagina and intestine. In April 2021, she shared that the cancer was “gone” after the surgery. In a new interview with The Times, Emin, 60, explained that upon her diagnosis, she was told that there was no guarantee the surgery would be successful in removing the cancer. At the time of her diagnosis, Emin said that she had feared being “dead by Christmas”. As a result, the Turner Prize nominee explained: “I totally accepted death – absolutely, totally.” “I think accepting death on such a profound level was what’s kept me alive,” she said. “I thought, you know what? Death looks after itself. We all die – now I’ll look after living. “I realised that my life has never really been living. I’ve been just dying. I’ve been so nihilistic. I thought, this is gonna change – if I get through this I want to look forward to things and I want to be present.” Emin, 60, now has a stoma (an opening on the abdomen connected to the urinary system allowing waste to be diverted out of the body) and uses a urostomy bag, which she will need to use for the rest of her life. On International Women’s Day in March, Emin penned a powerful personal essay in The Independent about her relationship with her body after surgery. Here, the artist admitted that she “hated” her bag, “but most days I’m philosophical; knowing that it keeps me alive”. She recalled: “One of my greatest golden moments was when my entire bag came off in Chanel on Bond Street: a tsunami of p*** cascading down my body crashing to the champagne-carpeted floor. Everyone was lovely and understood, Chanel even sent me a beautiful bouquet of flowers.” For the article published in The Independent, Emin created an exclusive acrylic on canvas artwork, titled “Marriage to Myself”. She also shared a candid photograph of herself standing in front of a full-length mirror with her white urostomy bag visible. While Emin works almost exclusively in the paint medium now, in June she unveiled three bronze doors that she secretly worked on for the re-opening of the National Portrait Gallery following a substantial £44m redevelopment. Etched in individual panels on the doors are 45 female faces, which Emin explained were inspired by facets of her “soul”. Emin said that her arrangement with the National Portrait Gallery was that she was not paid for the work (the gallery only paid the production fees), in exchange for total creative freedom. “It wasn’t a commission,” she explained. “I did it for free. I think the gallery wants to push the idea of portraiture in a different way. “There’s so many different ways to experience somebody’s, let’s say, soul. It doesn’t just have to be what they look like. It could be a portrait of the soul, for example. It could be lots of different things. So I think they wanted it to move away from the idea of classic portraiture. To stretch it.”

Tracey Emin has opened up about “totally accepting death” when she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of bladder cancer in 2020.

In June 2020, visual artist Emin was diagnosed with cancer, and subsequently underwent a series of major surgeries, including a full hysterectomy, as well as the removal of her urethra, bladder, lymph nodes, and part of her vagina and intestine. In April 2021, she shared that the cancer was “gone” after the surgery.

In a new interview with The Times, Emin, 60, explained that upon her diagnosis, she was told that there was no guarantee the surgery would be successful in removing the cancer. At the time of her diagnosis, Emin said that she had feared being “dead by Christmas”.

As a result, the Turner Prize nominee explained: “I totally accepted death – absolutely, totally.”

“I think accepting death on such a profound level was what’s kept me alive,” she said. “I thought, you know what? Death looks after itself. We all die – now I’ll look after living.

“I realised that my life has never really been living. I’ve been just dying. I’ve been so nihilistic. I thought, this is gonna change – if I get through this I want to look forward to things and I want to be present.”

Emin, 60, now has a stoma (an opening on the abdomen connected to the urinary system allowing waste to be diverted out of the body) and uses a urostomy bag, which she will need to use for the rest of her life.

On International Women’s Day in March, Emin penned a powerful personal essay in The Independent about her relationship with her body after surgery. Here, the artist admitted that she “hated” her bag, “but most days I’m philosophical; knowing that it keeps me alive”.

She recalled: “One of my greatest golden moments was when my entire bag came off in Chanel on Bond Street: a tsunami of p*** cascading down my body crashing to the champagne-carpeted floor. Everyone was lovely and understood, Chanel even sent me a beautiful bouquet of flowers.”

For the article published in The Independent, Emin created an exclusive acrylic on canvas artwork, titled “Marriage to Myself”. She also shared a candid photograph of herself standing in front of a full-length mirror with her white urostomy bag visible.

While Emin works almost exclusively in the paint medium now, in June she unveiled three bronze doors that she secretly worked on for the re-opening of the National Portrait Gallery following a substantial £44m redevelopment.

Etched in individual panels on the doors are 45 female faces, which Emin explained were inspired by facets of her “soul”.

Emin said that her arrangement with the National Portrait Gallery was that she was not paid for the work (the gallery only paid the production fees), in exchange for total creative freedom.

“It wasn’t a commission,” she explained. “I did it for free. I think the gallery wants to push the idea of portraiture in a different way.

“There’s so many different ways to experience somebody’s, let’s say, soul. It doesn’t just have to be what they look like. It could be a portrait of the soul, for example. It could be lots of different things. So I think they wanted it to move away from the idea of classic portraiture. To stretch it.”