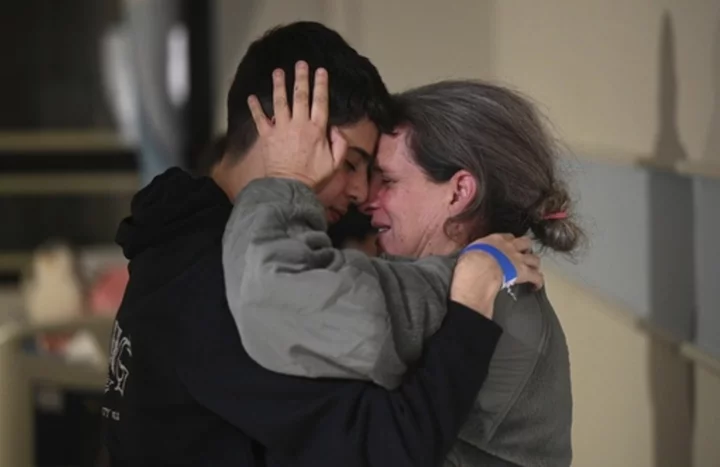

Abdul Hussein wipes away tears as he describes the day waves churned by Cyclone Mocha took his wife and three daughters from him.

His family -- all 11 of them -- had huddled together in their house in Sittwe, on the coast of Myanmar's Rakhine state, as ferocious winds intensified overhead.

"When the water started to flood, I held my small granddaughter very tightly," Hussein said.

As the water rose, the family ran to escape the storm surge but they got separated in the chaos. Most of them made it to higher ground, but his wife and three of his daughters ages 20, 18 and 11, were swept away.

"The water took them," Hussein said, distraught.

Hussein said he found their bodies when the cyclone subsided, and buried them.

Hussein and his surviving children and grandchildren are now without proper shelter or food. They have spent the past few nights in a shack cobbled together from what was left of their house. Everything around it was razed.

The children, he said, cry all night for their mother and sisters.

"I'm thinking only about them, I can't even eat, I can't even do anything," Hussein said, adding that he has had to beg for food for the children.

Coastal areas in Rakhine bore the brunt of Cyclone Mocha's winds, which tore over the state at over 200 kilometers per hour (195 mph) on Sunday, as one of the strongest storms to ever hit Myanmar.

Video and witness accounts show widespread devastation, with entire villages wiped out, shelters destroyed and piles of debris stretching over miles.

More than 400 people are estimated to have died, according to Myanmar's shadow National Unity Government, but the true toll and extent of the destruction is hard to know due to flooding, blocked roads and downed communications that have made access difficult.

A massive clean-up operation is underway for the millions of people affected by the storm, but clean water supplies and fuel are running low, and there is a critical need for shelters, food, medicine and healthcare services, according to the UN's humanitarian office (OCHA).

Aid agencies say they have finally begun reaching affected communities, a week after the cyclone hit and following claims Myanmar's military junta had been impeding access.

"Humanitarian assistance has begun reaching people affected by Cyclone Mocha in Rakhine State," the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said in a recent update.

"In recent days, initial humanitarian supplies have been transported via trucks... and humanitarians are exploring a range of approaches to try and move supplies to the impact zone from inside and outside the country, pending approval," OCHA said.

Emergency food has been delivered to cyclone shelters and humanitarian workers are now trying to gauge the full impact of the cyclone in areas where they have access, it added.

"However, there is still a shortage of fuel -- particularly for essential public services such as health facilities and water treatment. Other critical needs include shelter, food aid, medical supplies and healthcare services."

Crisis upon crisis

While western Rakhine state took a direct hit from the cyclone, the UN estimates 150,000 people in the country's northwest were also heavily affected.

Houses, schools and hospitals were destroyed across Chin state, and about 85,000 people in Sagaing region were impacted -- a situation exacerbated by ongoing conflict and the presence of troops hindering access to safe shelter, UN OCHA said.

Since the Myanmar military seized power in a coup in 2021, the country has been rocked by violence and instability. Fighting between junta troops and resistance groups under the People's Defense Forces (PDF) unfolds almost daily across the country.

One resident from Magway, where around 11,000 households were affected by the storm, said her husband died in flooding caused by Cyclone Mocha.

She said they were moving their belongings away from the floodwaters in the forest after they had been forced to flee what she said was military fire.

"We were getting our belongings back from the jungle where we hide from the military soldiers. When that happens, there were gun shots around so we had to hide," said the resident from Pauk township, who did not want to be named for security reasons.

Her husband had made her return home first with the cart while he went back to save their dog.

"He told me that he will to try to rescue the dog that was swept away by the current. Even though I told him not to go, he still left," she said.

She said neighbors helped her search and they later found his body.

"With gunshots everywhere and with two old people and one child, I don't know what to do," she said.

'Absolute brink'

Concerns are high for thousands of vulnerable people because Rakhine is a largely impoverished and isolated state, which in recent years has been the site of widespread political violence.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced in the state due to the protracted conflict, many of them members of the stateless Rohingya minority group, long persecuted in Myanmar.

Rohingya in Rakhine are mostly confined to camps akin to open air prisons, where authorities place strict controls on their movement, as well as access to schooling and health care.

"Rohingya and Rakhine communities alike are heavily impacted by conflict and successive humanitarian crises, relying almost entirely on humanitarian assistance for their survival," said Paul Brockmann, Medecins Sans Frontieres' operations manager for Myanmar.

"The impact of Cyclone Mocha has pushed people's coping mechanisms in Rakhine state to the absolute brink."

Brockmann said the scale of the medical humanitarian needs created by the storm are "enormous," and many of their mobile clinics have been destroyed, cutting people off from essential health care.

"In the townships of Sittwe, Rathedaung, Buthidaung and Maungdaw, damage has been extensive. In Rathedaung we estimate that 90% of homes in each village have been destroyed. People are desperate to repair their homes as the monsoon season is fast-approaching," he said.

Of particular concern is Pauktaw township, south of the capital Sittwe, where people were without assistance for four days, according to Brockmann.

The area is "only accessible by boat" and is home to an estimated 26,500 internally displaced people who have been living in camps for 12 years.

"Very little is known about their welfare or that of communities in the surrounding villages," Brockmann said.