In Courtroom No. 29, a gray, musty cubbyhole of a space wedged into the heart of Hong Kong’s tony banking district, Judge Linda Chan presides over China’s great financial reckoning.

One after the other, the high-powered attorneys and executives of distressed real-estate developers — the behemoths that had once powered the economic boom that made China the envy of the world — come before her to plead for their financial lives: China Evergrande Group, Sunac China Holdings, Jiayuan International Group, Kaisa Group Holdings.

Never before has there been such a wave of Chinese corporate defaults on bonds sold to foreign investors. And never in recent memory has a bankruptcy judge in Hong Kong, the de-facto home for such cases, earned a reputation for holding deadbeat companies to account quite like Chan.

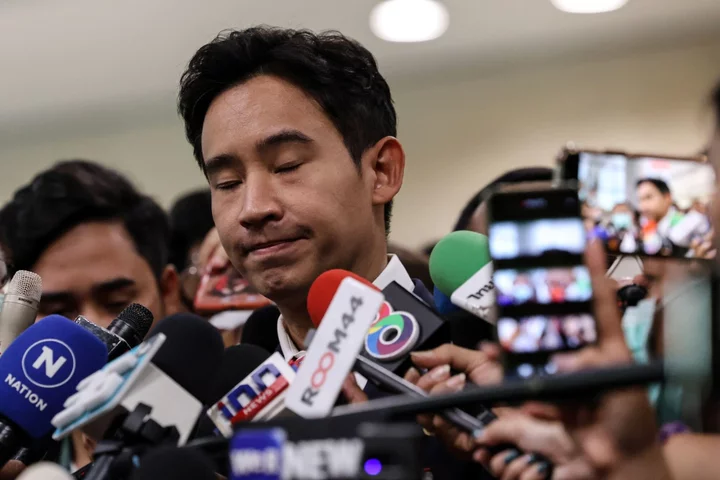

Chan, 54, has displayed an unwavering determination to give creditors a fair shot at recouping as much of their money as they can. One morning in early May, she shocked the packed courtroom by suddenly ordering the liquidation of Jiayuan. She had peppered the company’s lawyers that day as they tried, unsuccessfully, to explain why they needed more time to iron out their debt restructuring proposal.

And then, late last month, Chan put lawyers for Evergrande, the most indebted developer of them all, on notice: Either turn over a concrete restructuring proposal in five weeks or face the same fate as Jiayuan.

“This is really the last adjournment,” Chan told them.

More companies are almost certain to land in her court in coming months. One candidate: Country Garden Holdings Co., which at its peak was the top developer in China. The company has already defaulted on some of its $186 billion of liabilities.

Its smaller rivals were just starting to sink into financial trouble when Chan, having risen through the court over the years, was named the main judge for corporate and bankruptcy cases. This was back in 2021, when President Xi Jinping’s push to pierce the country’s property bubble was in full swing. Xi’s team wanted to bring down home prices to discourage financial speculation and avert social unrest. The property builders turned out to be collateral damage.

Some foreign creditors have chosen Hong Kong courts to try to shut down and liquidate developers that defaulted because the city’s common law system is familiar to them and fosters confidence. But whether Chan’s orders are carried out back on the mainland, where most of the developers’ assets are located, is the multi-billion dollar question.

Authorities struck an agreement a couple years ago that paved the way for some Chinese cities to recognize Hong Kong insolvency proceedings in a pilot program. Its implementation so far, though, has been spotty. The deal “has not achieved its stated objective,” says Wee Meng Seng, an associate professor at National University of Singapore.

And so this will leave executives at the bankrupt companies to ultimately take their cues from the Chinese government. It’s a crucial, and thorny, matter that’s coming to a head as Chan plows through the docket of cases piled up on her desk: Do independent rulings made by a court in Hong Kong carry the same weight in China as those made by a court in, say, Shanghai or Shenzhen?

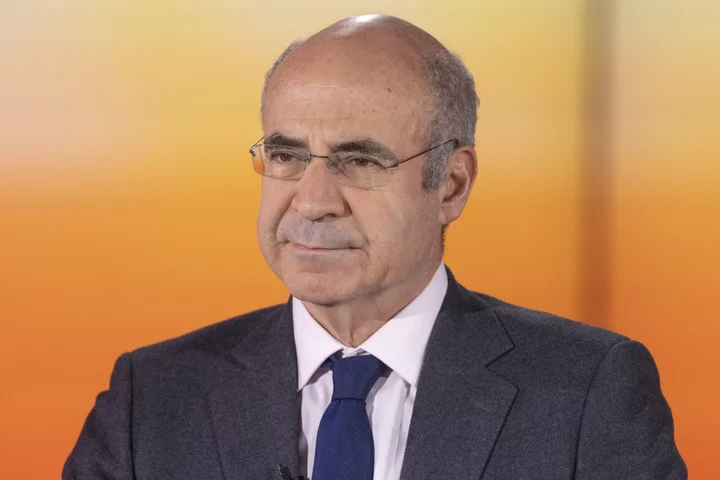

To Fred McMahon, a resident fellow at the Fraser Institute in Vancouver, the mere question highlights the extent to which tensions remain between the city and the mainland. “It says something about the state of law in Hong Kong,” McMahon says. He suspects Beijing will ignore Chan’s orders if they clash with its policy objectives.

A spokesperson for Hong Kong’s government said in a statement that the recognition of Hong Kong insolvency proceedings “is something novel in the Mainland, and we understand that Mainland courts are accumulating experience in handling the relevant applications and granting the relevant orders.” Hong Kong’s Department of Justice is taking steps to strengthen communication with counterparts in China, the spokesperson said. “The smooth implementation of any cross-border mechanism requires constant communication between the two sides.”

A spokesperson for the city’s judiciary system said that under the “One Country, Two Systems” principle, which establishes Hong Kong’s relationship with China, “the rule of law and judicial independence in Hong Kong are guaranteed under the Basic Law.” Several articles of the Basic Law “specifically provide that the judicial power, including that of final adjudication, vested with the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, is to be exercised by the Judiciary independently, free from any interference,” the spokesperson said in a statement.

The constitutional duty of judges in Hong Kong “is to exercise their judicial power independently and professionally in every case brought to the court, strictly on the basis of the law and evidence, and nothing else,” according to the spokesperson.

China’s Foreign Ministry referred questions to the “relevant ministry” without providing further details.

Chan declined to comment for this story.

Bondholders are quick to praise Chan. She’s given them hope even if they have so far benefited little from her efforts.

There are no outward signs, for instance, that the liquidation of Jiayuan, a developer that mainly operates in eastern China, is moving forward much. Its defaulted bonds, like those issued by Evergrande, Kaisa and Logan Group Co. trade at less than 10 cents on the dollar in overseas markets, an indication that for all the excitement surrounding Chan, creditors are resigned to getting back just a fraction of their initial investment.

Moreover, by international standards, debt restructurings still unfold at a glacial pace here, the result in part of the fact that the city lacks a clear-cut bankruptcy mechanism akin to Chapter 11 in the US. (Hong Kong is trying to create a law to fill this void.) Evergrande has been in default and working on terms of a restructuring deal for nearly two years now. Still, Chan has injected a sense of urgency in the courtroom that was rarely on display before her arrival, putting all lawyers and bankers who come before her on edge. Some of them get visibly rattled under her intense questioning.

“Chan has been decisive in the winding-up court,” says Jonathan Leitch, a Hong Kong-based partner at law firm Hogan Lovells International LLP. “She’s sending a helpful message for creditors.”

That Chan is a woman operating in Hong Kong’s male-dominated legal and financial world makes her crusade all the more striking. She was named to the group of senior counsels, who are veteran lawyers appointed by Hong Kong’s chief justice, before she joined the court in 2013. Currently only 14 of the city’s 107 practicing senior counsels are women.

Chan — and her high-profile cases — have become the talk of Hong Kong’s financial district. Spectators pack into the courtroom to watch her deliberate in her trademark soft-spoken, even-tempered manner.

They turned up early on the morning of Oct. 30 — the day she handed out the ultimatum to Evergrande — and chatted excitedly before the proceedings began. “I’m here to witness history,” one of them exclaimed. By the time Chan strode in, they were spilling out into the hallway. They hushed to attention as she took her seat overlooking the dimly lit chambers.

Hong Kong, UK

Born in Hong Kong, Chan studied business and law in the city and the UK. She opened her own private practice in 1998, just as the Asian financial crisis was driving scores of companies into bankruptcy — a period, she has said, that feels similar to what’s playing out in her courtroom now.

Over time, Chan would make a name for herself in Hong Kong legal circles as an expert in corporate bankruptcies and liquidation. One specialty: representing creditors who had invested in bankrupt companies that were technically domiciled in far-flung tax havens, a legal tactic that made seizing their assets even more difficult.

That experience, people who know her say, helped her appreciate as a judge the uphill battle creditors face in Hong Kong courts. And it led to one of the bigger milestones in her time on the bench, when she ruled that these offshore companies had to adhere to judgments in Hong Kong.

Chan has been “very successful” on this, says James Wood, a lawyer in Hong Kong who specializes in restructuring and insolvency. She’s achieved “excellent results using the Hong Kong legal machinery” to allow investors to go after assets previously out of their reach.

Chinese companies rarely tapped overseas bond markets until the boom years of the aughts, when the country became the engine for global economic growth. The nation’s financial assets were suddenly in hot demand, and Hong Kong became the go-to legal jurisdiction of choice for corporate bondholders when trouble arose.

There were sporadic defaults here and there over the years, but it wasn’t until the bursting of the property bubble two years ago that things went wrong enough to truly put the legal system to the test.

Since then, traders have marked down the value of China’s junk dollar bonds, mostly issued by developers, by $132 billion. The average price in secondary markets on such bonds today is about 80 cents on the dollar. (Some fetch as little as one cent.) The average yield is now more than 14%, double its level four years ago, a Bloomberg index shows.

For those builders still trying to stave off bankruptcy, the math is daunting. Collectively, they owe a combined $14 billion by the end of next year and another $15 billion the following year.

The clock is ticking for the lawyers and executives at Evergrande, too. On Dec. 4, they have to walk back into Linda Chan’s chambers, squeeze through the crowd of on-lookers and turn over a restructuring plan she finds acceptable.

--With assistance from Alan Wong, Lucille Liu, Emma Dong and Kiuyan Wong.