Investigators are trying to solve a mystery about the origin of last month's deadly Maui wildfire: How did a small, wind-whipped fire sparked by downed power lines and declared extinguished flare up again hours later into a devastating inferno that killed at least 97 people?

Here are the key takeaways of an Associated Press investigation into the probe:

WHAT DO THEY THINK HAPPENED?The answer may lie in an overgrown gully beneath Hawaiian Electric Co. power lines and something that harbored smoldering embers from the initial fire Aug. 8 before rekindling in high winds into a wall of flame that quickly overtook the town of Lahaina, destroying thousands of structures and forcing residents to jump into the ocean to escape.

Investigators led by the federal bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and Maui County have declined to comment on specifics of the probe.

But The Associated Press reviewed more than 950 photos taken last month showing investigators combing through the gully area and examining several items that could be possible ignition sources for the rekindled fire. They included a heavily charred, hollowed 4-foot-tall stump of a utility pole, two heavily burned trees and the remains of an old car tire.

While experts cautioned the gully was full of places where embers could fester, they noted that these larger items stood out because the second fire erupted hours later, and stumps and roots have been known to harbor embers and keep them glowing a long time, in some cases weeks.

WHAT ELSE IS GETTING SCRUTINY?As investigators sift through blackened debris to explain the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century, one fact has become increasingly clear: Hawaiian Electric's right-of-way was untrimmed and unkempt for years, despite being in an area classified as being at high risk for wildfires.

Aerial and satellite imagery reviewed by the AP show the gully has long been choked with thick grass, shrubs, small trees and trash, which a severe summer drought turned into tinder-dry fuel for fires. Photos taken after the blaze show charred foliage in the utility’s right-of-way still more than 10 feet high.

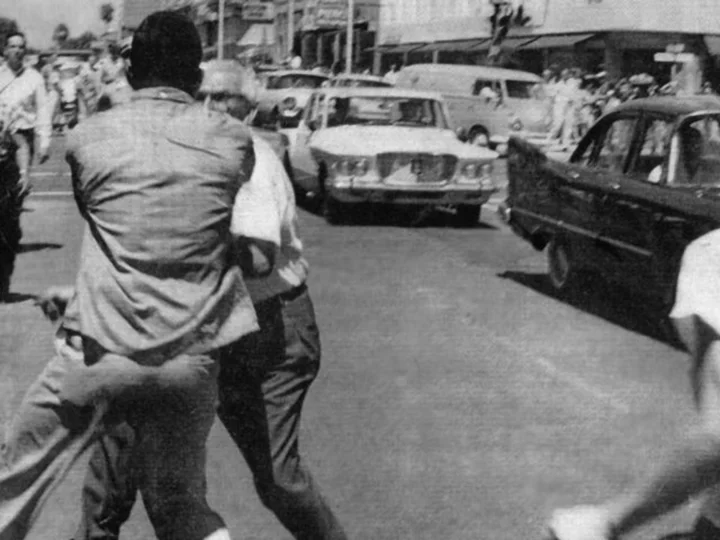

“It was not manicured at all,” said Lahaina resident Gemsley Balagso, who has lived next to the gully for 20 years and never saw it mowed. He watched and took video Aug. 8 after the flames reignited there and were stoked by winds from a hurricane churning offshore into a raging inferno that grew too fast for firefighters to stop.

The focus on Hawaiian Electric’s role in managing brush in its right-of-way could strengthen claims of negligence against the utility, which is facing an onslaught of lawsuits.

WHAT DOES THE UTILITY SAY?Hawaiian Electric has acknowledged its downed lines caused the initial fire but has argued in court filings it couldn’t be responsible for the later flare-up because its lines had been turned off for hours by the time the fire reignited and spread through the town. The utility instead sought to shift the blame to Maui County fire officials for what it believes was their premature, false claim that they had extinguished the first fire. The county says the firefighters are not to blame.

Asked about the overgrown gully, Hawaiian Electric said in a statement to AP that the right-of-way allows it “to remove anything that interferes with our lines and could potentially cause an outage.”

“It generally does not give us the right to go on to private property to perform landscaping or grass-mowing,” the company said.

National standards don’t specifically call for utilities to clear away vegetation unless it is tall enough to reach their lines, but fire science experts say utilities should go beyond that in wildfire areas to remove excess brush that could fuel a fire.

WHAT IS THE UTILITY'S RECORD?Hawaiian Electric has a history of falling behind on what the electricity industry calls “vegetation management.”

A 2020 audit of Hawaiian Electric by an outside consulting firm found the company failed to meet its goals for clearing vegetation from its rights of way for years, and the way it measured its progress was inadequate and needed to be fixed “urgently.” The 216-page audit by Munro Tulloch said the utility tracked money it spent on clearing and tree trimming but had “zero metrics” on things that really mattered, such as the volume of vegetation removed or miles of right-of-way cleared.

Hawaiian Electric said in its statement to the AP that since that audit it has “completely transformed” its trimming program, spending $110 million clearing vegetation in the past five years, using detailed maps to find critical areas and tracking outages caused by trees and branches.