The Supreme Court ruled Thursday that the late Andy Warhol infringed on a photographer's copyright when he created a series of silk screens based on a photograph of the late singer Prince.

The ruling was 7-2, with Justice Elena Kagan penning a stinging dissent and arguing that the opinion will "stifle creativity of every sort."

The court rejected arguments made by a lawyer of the Andy Warhol Foundation (the artist died in 1987) that his work was sufficiently transformative so as not to trigger copyright concerns.

The opinion has been closely anticipated by the global art world watching to see how the court would balance an artist's freedom to borrow from existing works and the restrictions of copyright law.

"Goldsmith's original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists," Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion, referring to Lynn Goldsmith, the photographer at the center of the case.

At issue is the so-called "fair use" doctrine in copyright law that permits the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.

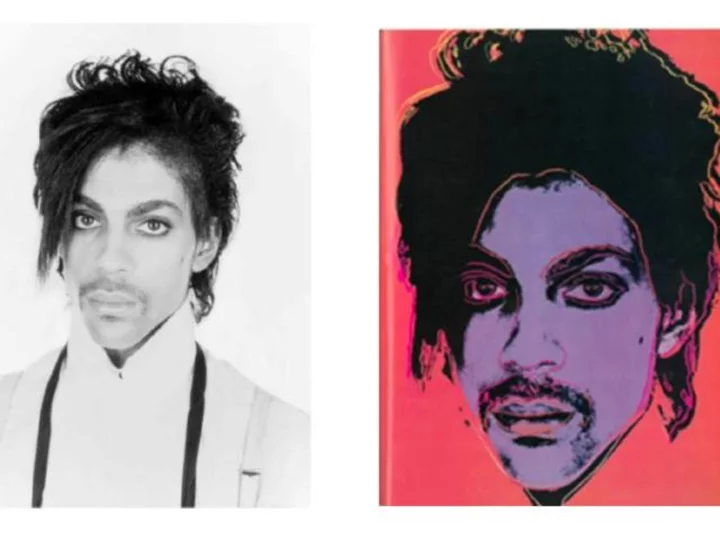

Here, Sotomayor said "fair use" should not apply to an image Warhol created that is referred to as "Orange Prince."

Sotomayor focused on the commercial purpose of both works. She said that both Goldsmith's photo and Warhol's silk screen are used to depict Prince in magazine stories and share "substantially the same purpose," even if Warhol altered the artist's expression.

"If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes," and they are both used in a "commercial nature," Sotomayor said, it is unlikely that "fair use" applies.

Sotomayor conceded that if the "purpose and character" of the works was "sufficiently distinct" -- the case may have come out differently.

In a rare move for a Supreme Court opinion, Sotomayor included depictions of both works to illustrate her point.

"Although the majority opinion focuses on only one of the four factors courts are supposed to apply in determining when works of art can be fairly used by others, there's little question that the majority opinion will have a major impact on these kinds of reproductions -- making it harder for artists to repurpose the works of others even with meaningful differences (and not just reproduce them), without their permission," said Steve Vladeck, CNN Supreme Court analyst and professor at the University of Texas School of Law.

"Indeed, whether one thinks Justice Sotomayor's majority opinion or Justice Kagan's dissent has the better of the legal arguments, it's hard to disagree with Kagan that such an approach could 'stifle creativity' across a range of artistic media -- and that perhaps Congress ought to revisit whether this is the best outcome," he said.

Kagan dissent: Prior precedent in 'shambles'

In the case at hand, a district court ruled in favor of Warhol, basing its decision on the fact that the two works in question had a different meaning and message. But an appeals court reversed -- ruling that a new meaning or message is not enough to qualify for fair use.

In reviewing the case, the justices had to provide a proper test that protects artist's rights to monetize their work, but also encourages new art and expression. During oral arguments, they did not seem enthusiastic about the lower court decision, but struggled to articulate a proper standard.

Kagan, joined in dissent by Chief Justice John Roberts, wrote in her dissent that Thursday's opinion leaves the court's prior precedent in "shambles."

Both Sotomayor and Kagan are liberal Barack Obama nominees, but had widely different views Thursday.

Kagan said that the majority looked past the fact that the silk screen and the photo do not have the same "aesthetic characteristics" and did not "convey the same meaning." All the majority cared about, she said, was the commercial purpose of the work.

Such an approach, Kagan argued, "ill serves copyright's core purpose."

"Both Congress and the courts have long recognized that an overly stringent copyright regime actually stifles creativity by preventing artists from building on the works of others," she wrote.

"Artists don't create all on their own; they cannot do what they do without borrowing from or otherwise making use of the work of others," she said.

Kagan said that Warhol's "eye-popping" silk screen of Prince "dramatically" altered Goldsmith's photograph and she called Warhol the "avatar of transformative copying."

"There is precious little evidence in today's opinion," she lamented, "that the majority has actually looked at these images, much less that it has engaged with expert views of their aesthetics and meaning."

She peppered the opinion with other references -- a "slew of works," she said -- where artists borrowed from one another, including William Shakespeare, Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson. Kagan went as far as including a colored photograph of Giorgione's Sleeping Venus from 1510 and a work by Titian called Venus of Urbino in 1538 that are strikingly similar.

Kagan said the new opinion will "impede new art and music and literature" and that it will "thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge."

She added: "It will make our world poorer."

Tone and tension at end of term

The case was argued all the way back in October, and presumably because both sides delved so deeply into the intricacies of copyright law and the art market, it was released later in the term than many expected.

That said, Kagan's dissent reflects some tension with her liberal colleague Sotomayor and the others in the majority, consistent with the fact that the justices are racing to decide major issues before the end of June at a time when tensions can run high.

"As readers are by now aware, the majority opinion is trained on this dissent in a way majority opinions seldom are," Kagan wrote. She pointed specifically to Sotomayor's dig at Kagan in one portion of the opinion when Sotomayor wrote that her opinion won't "snuff out the light of Western civilization, returning us to the Dark Ages of a world without" Titian and Shakespeare.

Sotomayor's tone was not lost on Kagan.

Quoting Sotomayor, she wrote: "After all, a dissent with 'no theory' and 'no reason' is not one usually thought to merit pages of commentary and fistfuls of comeback footnotes."

Kagan said she hoped the public would read her dissent carefully: "I'll take my chances on readers' good judgment."

The Prince Series and Lynn Goldsmith photographs

"Fair Use protects the First Amendment rights of both speakers and listeners by ensuring that those whose speech involves dialogue with preexisting copyrighted works are not prevented from sharing that speech with the world," a group of art law professors who supported the Andy Warhol Foundation told the justices in court papers.

Lawyers for the Warhol Foundation contended that the artist created the "Prince Series" -- a set of portraits that transformed a preexisting photograph of the musician Prince -- in order to comment on "celebrity and consumerism."

They said that in 1984, after Prince became a superstar, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create an image of Prince for an article called "Purple Fame."

At the time, Vanity Fair licensed a black and white photo that had been taken by Goldsmith in 1981 when Prince was not well known. Goldsmith's picture was to be used by Warhol as an artist reference.

Goldsmith -- who specializes in celebrity portraits and earns money on licensing -- had taken the picture initially while on assignment for Newsweek. Her photos of Mick Jagger, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan and Bob Marley are all a part of the court's record.

Vanity Fair published the illustration based on her photo -- once as a full page and once as a quarter page -- accompanied by an attribution to her. She was unaware that Warhol was the artist for whom her work would serve as a reference, but she was paid a $400 licensing fee. The license stated "no other usage rights granted."

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol went on to create 15 additional works based on her photograph. At some point after Warhol's death in 1987, the Warhol Foundation acquired title to and copyright of the so-called "Prince Series."

In 2016, after Prince died, Conde Nast, Vanity Fair's parent company, published a tribute using one of Warhol's Prince Series works on the cover. It is referred to as "Orange Prince." Goldsmith was not given any credit or attribution for the image. And she received no payment.

Upon learning about the series, Goldsmith recognized her work and contacted the Warhol Foundation, advising it of copyright infringement. She registered her photo with the US Copyright Office.

The Warhol Foundation -- believing that Goldsmith would sue -- sought a "declaration of noninfringement" from the courts. Goldsmith countersued with a claim of copyright infringement.

Limiting freedom of expression?

In appealing the case on behalf of the Warhol Foundation, lawyer Roman Martinez argued that the appeals court had gone badly wrong by forbidding courts from considering the meaning of the work as a part of a fair use analysis.

He warned the court that if it were to embrace the reasoning of the appeals court, it would upend settled copyright principles and chill creativity and expression "at the heart of the First Amendment."

According to Martinez, copyright law is designed to foster innovation and sometimes builds on the achievements of others.

Martinez stressed that the fair use doctrine -- "which dates back at least to the 19th century" -- reflects the recognition that a rigid application of the copyright statute would "stifle the very creativity which that laws was designed to foster."

He noted that Warhol's works are currently found in collections across the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Smithsonian collection and the Tate Modern in London. From 2004 through 2014, Warhol auction sales exceeded $3 billion.

Martinez said Warhol made substantial changes by cropping Goldsmith's image, resizing it, altering the angle of Prince's face while changing tones, lighting and detail.

"While Goldsmith portrayed Prince as a vulnerable human, Warhol made significant alterations that erased the humanity from the image, as a way of commenting on society's conception of celebrities as products, not people," Martinez argued, adding, "The Prince series is thus transformative."

'Fame is not a ticket to trample other artists' copyrights'

Lisa Blatt, a lawyer for Goldsmith, told the justices a very different story.

"To all creators, the 1976 Copyright Act enshrines a longstanding promise: Create innovative works, and copyright law guarantees your right to control if, when and how your works are viewed, distributed, reproduced or adapted," she wrote in court papers.

She said that creators and multibillion-dollar licensing industries "rely on that premise."

She said that the Andy Warhol Foundation should have paid Goldsmith's copyright fees. Blatt argued that Warhol's work was almost identical to Goldsmith's own.

"Fame is not a ticket to trample other artists' copyrights," she said.

The Biden administration supported Goldsmith in the case.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar noted, for example, that book-to-film adaptations often introduce new meanings or messages, "but that has never been viewed as an independently sufficient justification for unauthorized copying." She said that Goldsmith's ability to license her photograph and earn fees has been "undermined" by the Warhol Foundation.

This story has been updated with additional details.