Every morning since the school year started, before teacher assistant Madelyn Cedeno shuts the front door of Peter A. Reinberg Elementary School at the start of classes, she peers out one last time.

She hopes she'll see Serabi Medina running late, with her playful smile, her big red hair flying and her father trailing just behind her. The teacher and student first bonded over their ginger hair when Serabi began kindergarten four years ago. "She just reminded me of me at her age with that color hair," Cedeno said. "I pretty much told her, 'All of us gingers around the world, we stick together in any kind of weather, so you and I are stuck together forever.'"

"We were the gingers of Reinberg," she said.

The two often chatted in the school hallways and in the mornings, when Cedeno stood outside the school to greet students. And every day, before Serabi walked into school, she would tell Cedeno she loved her.

They saw each other again in early August, after Serabi had finished a summer class she took before she was set to start fourth grade. Cedeno told her the upcoming school year would be fantastic. They hugged and said goodbye with their special, signature wave.

Less than a week later, the vibrant 9-year-old was shot and killed, allegedly by a neighbor, in front of her Chicago home -- one of at least 1,400 children and teens killed by a firearm so far in 2023, according to the Gun Violence Archive. Firearms became the No. 1 killer of children and teens in America in 2020, surpassing motor vehicle accidents, which had long been the leading cause of death among America's youth, federal data shows.

Serabi had been riding her scooter and had just returned from a nearby ice cream truck carrying two ice-creams: one for herself and one for her dad, who was outside with her. As she reached the door of their apartment building, authorities say neighbor Michael Goodman approached her and fired his gun, fatally striking Serabi in the head.

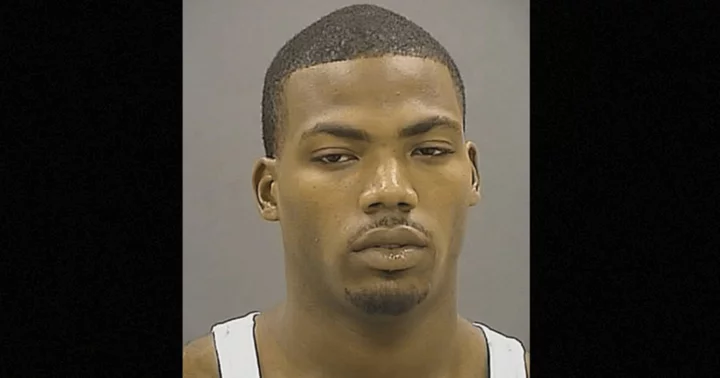

He has pleaded not guilty and is being held without bond on first-degree murder charges. Goodman's public defender, Kathryn Lisco, told CNN Goodman has been "plagued by debilitating and documented mental health issues over the course of his life."

"The real question we should be asking is why, despite Michael Goodman's mental health history was he ever able to legally obtain a gun?" Lisco said.

At every court hearing, Serabi's family has been there, waiting for justice. It's been rough, her father says. But that doesn't even begin to describe it: Serabi was his "light," the little girl he had devoted his life to after his partner, Serabi's mom, was shot and killed five years ago right in front of their eyes. Chicago police say that investigation is ongoing, and no suspect is in custody.

"Once I lost her mom, I lost half of myself, so my focus was all on my daughter," Michael Medina told CNN in a recent interview.

"She was just a beautiful girl, my light. She was my life."

Braids and press-on nails

Even for those who knew her best, putting Serabi into words isn't easy: She was unstoppable.

Serabi was always happy, always active. She was a dodgeball champion, a YouTube enthusiast, an animal lover. She didn't shy away from saying hello to strangers.

"She was full of life," her cousin, Jaleesa Medina, 29, said. "She wouldn't need music to dance." She loved to dress up during Halloween -- last year, she dressed up in a Ghostbusters theme, her cousin recalled.

And she was creative, often putting press-on nails and pouring time into braiding her hair and coming up with new hairstyles, her father recalled. She'd often ask Medina for help, directing him to hold one braid as she worked on another. "Daddy, just do it, you can do it, don't worry," she'd encourage him.

Serabi was fearless, never afraid to learn something new or stand up to someone decades older than her when she felt picked on. She was always cracking jokes to make others laugh, and often enjoyed sassy exchanges with family members, they said. At school, even the eighth graders knew her, her father says, and she was always trying to be "a comedian."

"She walked in the room with a big smile on her face and everyone just kind of turned and looked," her principal, Edwin Loch, said.

Five days after her death, Loch helped organize a candlelight service in her honor. He asked everyone to wear purple, her favorite color. More than a hundred people gathered to say goodbye.

"She was never mean to anybody, always wanted to be the person that got people together, and have fun," Loch recalled. "She just wanted to live."

'She raised us'

To John Hogue Jr., her half-brother, Serabi was, first and foremost, his "baby sister."

John, 16, was the second person to ever hold her when she was born. He fed her when she was a baby, rocked her to sleep and watched cartoons like "Paw Patrol" and Barbie, just to spend time with her. When their mom, Blanca Miranda, was still alive, the three of them would often go to water parks and the movies.

He had felt excited, he told CNN, to be a big brother to Serabi and wanted to take care of her. But often, it felt like she took care of him, he said.

"She was always caring, and if something happened, she'd be there and help me talk," John, a high school junior, said. "She'd talk like a grown-up, she was loving like a grown-up."

It's something many of her loved ones point out: Despite her young age, Serabi always seemed wise beyond her years, and quick to offer words of comfort to those who needed it most, though she was hurting from her own loss. Serabi saw her mother's fatal shooting, alongside John and her father, when she was just 4 years old.

"I don't know if it was like a little sister feeling that she would get inside, but it seemed at times when I'd be hurting the most, she would reach out and say, 'Hey, I love you,'" Serabi's half-sister, Lacey Tatro, said. The two hadn't seen each other in years but would video call almost every night. "That was my best friend," Tatro said.

After her mother's killing, Serabi would also often console her aunt Juanita Miranda, Blanca's sister. "Mommy's okay," Serabi would remind her, urging her not to cry.

"She raised us," Miranda said. "She taught me to be strong in a lot of ways, no matter what. And she still teaches me to this day."

The two shared a special bond, Miranda said, since the very moment Serabi was born. "She came out with her eyes open, and I'll never forget that," she said of that moment. "She was just open to the world. She was my baby before I even had a daughter."

Together, they made YouTube videos that never got posted, did internet challenges, and regularly ordered their favorite drink: iced coffee, extra caramel. Three days before Serabi was killed, she spent the night with her aunt, and they ate snacks, scrolled through TikToks and watched the Barbie movie.

Her niece's loss, Miranda says, has left her deeply traumatized. But she's determined to join other family members in court once the trial in Serabi's killing begins. "I just want to know why," Miranda said.

A memorial for Serabi

At school, faculty members are preparing to dedicate a permanent memorial on the campus Serabi once roamed. The past two months have been very difficult, Cedeno says.

"Her reminder, her presence is very, very strong," she said. Mornings are the toughest.

At home, Medina misses his daughter's voice, the brief arguments they'd share in the morning as they got ready to start the day, their walks to school, their bike rides in the evenings. Since losing her mother, Serabi and her father had become inseparable. Even when he spent time fixing cars in their garage during the frigid Chicago winters, Serabi was there, passing him the tools.

"My baby was always with me," Medina said. "That's why I'm so lost now."

After she died, Serabi was laid to rest with her mother.

John said he promised her he'd visit every weekend, but the visits are devastating reminders of the two losses the teen has suffered in the past five years: his mom, and his only little sister.

"When I go over there, I cry," he said. "I just think about the times me and her had together."

"She always loved me, her big brother."