There are few, if any, leaders in the world who are publicly lashing out at central bankers more than Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

The reasons are increasingly evident as Brazilians feel the pinch of a weakening economy. Nine months after policymakers pinned benchmark interest rates at 13.75%, capping off a dozen rapid-fire hikes, household debt is lingering at a record, banks are gutting lending and corporate bankruptcies are rising.

Much of this pain is being inflicted by the design of central bank governor Roberto Campos Neto. Without it, he and his colleagues figure, demand in the economy won’t cool enough to get inflation fully back to the country’s target.

Read this story in Portuguese.

To Lula, however, this is nonsense. He’s singled out Campos Neto in his tirades, accusing the former bank executive of hampering the nation’s growth by making it too expensive for Brazilians to borrow money.

The feud between the two men is shining a light on a growing risk across the global economy. Brazil’s central bank may have pushed up interest rates earlier and higher than others, but almost all of them — from the Federal Reserve to the Bank of England — have hiked to levels that are uncomfortably high for politicians.

Calls for an end to rate hikes are mounting in capitols from Nairobi to Bogotá to New Delhi, threatening to undermine the autonomy that's so critical to central banks' fight against inflation.

"The truth is that inflation will take longer to come down in Brazil, and will take longer to come down pretty much everywhere,’’ said Silvia Matos, an economist at Fundacao Getulio Vargas, a local university and think tank. “This super-tight global monetary policy has created an environment more prone to disagreements between governments and central banks. It is a relationship that might become more rowdy."

Squeezed at Every Level

In Brazil, strain is evident at every level of the economy — from consumers to chief executives. That makes it easy for 77-year-old Lula, whose political career has spanned presidencies and prison sentences, to blame Campos Neto.

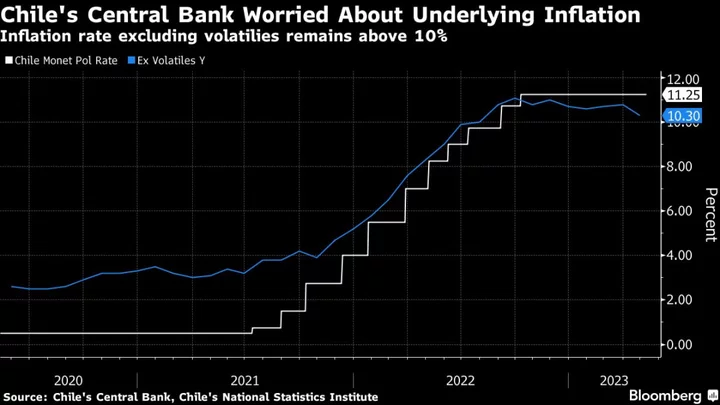

While inflation is already down more than half from last year’s peak of 12% — it came in at 4.2% in April — economists are split on whether it will keep cooling. That uncertainty is pushing Brazil’s central bank to keep its key rate at the highest in more than six years.

Headline inflation has seen a sharp slowdown, but core prices continue to rise at a fast pace, Campos Neto said this week, acknowledging Lula has the right to debate monetary policy.

Elevated borrowing costs are among the reasons that household debt in Brazil is lingering at an all-time peak and carmakers are closing production lines to avoid oversupply. The average interest rates on personal and homes loans in the nation are at 42% and 11%, respectively.

It’s gotten harder to borrow at a corporate level, too. Campos Neto’s rate hikes made local debt markets costlier even before dollar bond markets were chilled by the Federal Reserve’s most-aggressive monetary tightening cycle in a generation. New issuance out of Brazil — in both domestic and international capital markets — has plunged.

There were only about 90 bond deals out of Brazil this year through mid-May, mostly in reais, amounting to roughly $11 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That’s a drop of 51% compared to the same period a year earlier, the data show.

“The feeling that borrowing costs will may remain high for a while generates a lot of uncertainty,” said Leonardo Ono, a credit portfolio manager at Legacy Capital, a hedge fund with $7.2 billion in assets under management. “Companies will have to deal with tighter policy rates for longer than expected and, in a time like this, cash flow and balance sheet situation becomes worse.”

Banks have also been paring back lending, wary of taking on more risk exposure after retailer Americanas SA uncovered a $4 billion accounting hole that led to its shocking filing for bankruptcy protection. After last year’s hit from bad loans, Banco Bradesco SA said caution is needed with rates so high. Banco Santander Brasil SA is still nursing the wounds of a nearly 50% drop in first-quarter profits.

That’s left business to seek support from unexpected sources. Meatpacker Minerva SA’s financial chief, Edison Ticle, said earlier this month that the beef exporter sacrificed cash to help finance some of its suppliers that were struggling to acquire financing on their own.

“We needed to replace banks on financing our supply chain,” he said in an interview.

Corporate Trouble

The number of bankruptcy requests made by Brazilian companies in the first four months of the year has soared 34.1% compared to the same period a year earlier, according to corporate-data analysis firm Serasa Experian. As Daniel Pegorini, the chief executive officer of Valora Gestão de Investimentos, puts it, high rates mostly “accelerated the demise of companies that already had problems.’’

“There will be no quick short-term solution,’’ said Alberto Serrentino, vice president of the Brazilian Society of Retail and Consumption, a lobby group. “We need the prospect of an interest-rate cut and a normalization of the private credit market so that companies can breathe.”

Read More:

- Latin American Central Banks Fight Back Against Easing Calls

-

What’s Behind Lula’s Clash With Brazil’s Central Bank: QuickTake

-

Lula’s Jab at Central Bank Puts Traders on Edge Across Brazil

Toymaker’s Dilemma

Not even during the pandemic, said Marcelo Cardoso de Sa, the managing partner at a small Brazilian manufacturer called Light Toys, were things this bad. With retail sales sputtering, one of the toymaker’s top clients Marisa Lojas SA stiffed it on a 2 million reais ($395,000) bill — a huge sum for a stuffed-animal maker with 400 employees.

Desperate to keep his business running, Cardoso sought financing to cover the shortfall. But the three bank offers he got back were so expensive that he had to take out a personal loan to get the rate down to a level he could afford.

“Our financials have suffered,” he said, “but we will keep trying.”

Marisa, a fashion retailer, had been in talks for months with its own creditors before it finally stopped paying Light Toys. A representative for Marisa said the firm is talks with its suppliers to find a solution. The toymaker is still waiting to receive the payment.

Holding Out

The harder Brazilians are squeezed, the more emboldened Lula is getting — he’s started singling out Campos Neto in his tirades — and the more perilous the fight becomes to keep the central bank free from the kind of political meddling that’s wreaked so much economic havoc in the past.

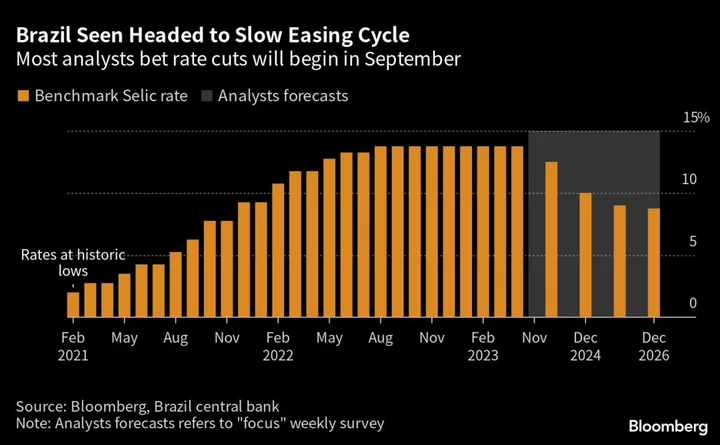

Even so, it’s likely just a matter of time until inflation eases enough for the central bank to loosen its grip on the economy. Traders in Brazil now price in the potential for interest rate cuts starting later this year.

For now, though, Campos Neto isn’t backing down.

He’s defended the central bank’s autonomy, which was only officially made into law in 2021, and staunchly advocated for the country’s inflation goals. While everyone wants lower rates, he's argued, the consequences of spiraling price increases would be far worse — especially in a country with a history of hyperinflation.

Brazil’s central bank didn’t mention future rate cuts in its most-recent meeting minutes. Instead, officials said they were “concerned” with expectations that consumer price increases will re-accelerate. As he and his team see it, core measures stripping out the most-volatile items — like food and energy — and analysts’ expectations for inflation need to ease before they can lower borrowing costs.

Lula, on cue, slammed Campos Neto for the decision.

“He has no commitment to Brazil,’’ the president said. “Brazilian retailers, businesspeople, workers can no longer stand this interest rate.’’

--With assistance from Barbara Nascimento, Daniel Carvalho, Leonardo Lara, Giovanna Bellotti Azevedo and Tatiana Freitas.

(Updates with recent comment from Campos Neto in tenth paragraph. A previous version of this story corrected the spelling ofNew Delhi.)

Author: Martha Viotti Beck, Felipe Saturnino and Maria Eloisa Capurro