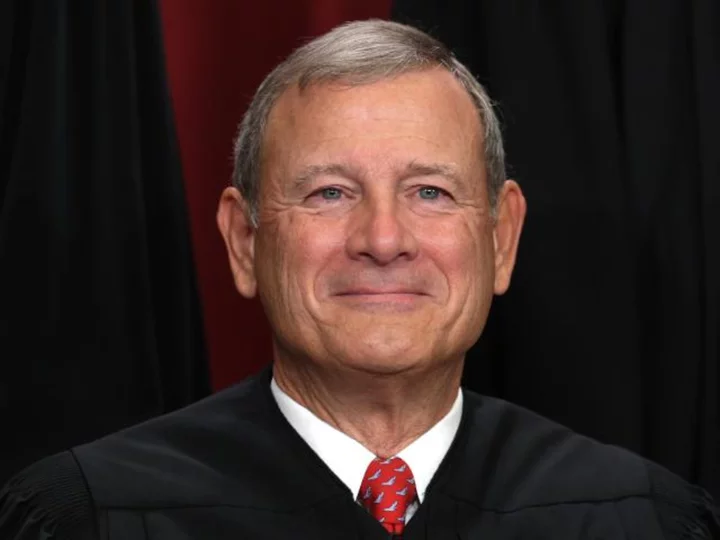

As he began reading excerpts of his decision eviscerating college affirmative action, in a hushed courtroom Thursday, Chief Justice John Roberts delivered on a singular long-held goal.

He had won a majority to roll back 45 years of Supreme Court precedent to further his view that race, for better or worse, should not matter.

"Racial classifications are simply too pernicious," Roberts said at the beginning of what would be 50 minutes of high drama in the courtroom.

The majority's rejection of race-based admissions practices at Harvard and the University of North Carolina -- programs replicated in schools nationwide -- amounts to a seismic reversal of court reasoning and regard for the value of campus diversity.

The decision was not unexpected, given that the right wing of the bench had been bolstered in recent years, including by three appointees of former President Donald Trump. And Roberts himself had been pressing for such an outcome for decades. "The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating based on race," he had written in a 2007 case.

Still, the full weight of the historic moment was felt in the white marble setting as Roberts, Sonia Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas all read excerpts of their opinions. Thomas, an African American who has opposed racial remedies and who joined the Roberts' decision, noted at the outset of his presentation that he rarely takes the unusual step of reading aloud a separate statement.

Sotomayor, the nation's first Hispanic on the high court, spoke for the dissenting justices, going on more than twice as long as Roberts. "The court's decision today is profoundly wrong," she declared, referring later to, "the court's own impotence in the face of an America whose cries for equality resound." The practices in dispute have historically created opportunities for Blacks, Hispanics and other minorities that have traditionally been underrepresented on campuses.

In seats below the elevated bench sat US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who had urged the justices to uphold college affirmative action, and her team from the Department of Justice. Most of the spectator benches were filled, as were the justices' special guest seats. Jane Sullivan Roberts, a lawyer and the wife of the chief justice, slipped into her place just as the nine justices were ascending the bench and opinions were to be announced.

'It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race'

Roberts has vigorously opposed racial remedies since his days as a young lawyer in the Ronald Reagan administration, in areas of the law from education to voting rights. Appointed to the Supreme Court in 2005 by then-President George W. Bush, Roberts has pushed the bench in a similar direction. He lamented in a 2006 redistricting case, "It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race."

Roberts has long questioned the value of classroom diversity and suggested the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education landmark opinion, which struck down the separate-but-equal doctrine and began America's school desegregation, prohibited assigning students based on race.

He reiterated a narrow interpretation of Brown on Thursday, writing, "The conclusion reached by the Brown Court was thus unmistakably clear: the right to a public education 'must be made available to all on equal terms.'" And the chief justice insisted that the case was premised on the notion that the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection guarantee forbids the use of race as a factor in deciding educational opportunities.

The three dissenting justices -- Sotomayor, joined by Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, the court's first Black woman -- disputed Roberts' interpretation of constitutional history and said in their opinion that "Brown was a race-conscious decision that emphasized the importance of education in our society."

At bottom, Roberts said, "the Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause." He was joined by Justices Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Brushing back arguments from the two universities about the comprehensiveness of their screening and its educational goals, Roberts told courtroom spectators that the arguments amounted to: "Trust us."

In his 40-page opinion, Roberts said Harvard and UNC engaged in racial stereotyping and lacked clear objectives as well as an end-point for their practices. "We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today," he said.

Sotomayor: 'No one is fooled'

The 68-year-old chief justice was born in Buffalo and reared in northern Indiana, where his father was an executive for Bethlehem Steel. Roberts' formative years were entwined with emerging affirmative action policies. (The phrase traces to the John F. Kennedy administration when government contractors were required to take "affirmative action" to avoid discriminating on the basis of race. Congress and President Lyndon B. Johnson followed through with more sweeping protections against race discrimination in the 1964 Civil Rights Act.)

In the 1970s, when Roberts was at Harvard, first as an undergraduate and then in law school, debates over faculty and student diversity roiled campus. Some administrators openly complained that the quest for a more diverse faculty could dilute academic standards.

The Supreme Court decided the milestone case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke when Roberts was at Harvard Law School. Allan Bakke, a White man who had served in Vietnam and been a NASA engineer, was rejected by the University of California at Davis medical school. He sued, saying he had been excluded because of the school's program that set aside a select number of places for racial minorities.

In the 1978 Bakke decision, the justices by a 5-4 vote (with splintered reasoning) upheld consideration of race as one of many factors in screening applications but forbade the use of quotas. Justice Lewis Powell, whose key vote bridged two four-justice blocs, sealed the outcome of the case; he justified the use of race in admissions based on a university's goal of a diverse student body, and he held up as a model Harvard's practice of using race as a "plus" factor for minority applicants.

The Supreme Court endorsed the Bakke decision in its 2003 ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger. By a 5-4 vote, the justices upheld a University of Michigan law school admissions program that looked at applicants' race among other individual criteria.

As Roberts referred to Grutter on Thursday, he minimized the decision's stated regard for campus diversity and minorities' participation in the civic life of the nation. Rather, he emphasized its cautions about the use of race and suggested deadlines: "We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today," Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote for the Grutter majority.

Roberts said a core principle of the case was that race-based admissions programs must end: "It was the reason the Court was willing to dispense temporarily with the Constitution's unambiguous guarantee of equal protection," he wrote.

Sotomayor accused Roberts of "cherry-picking language from Grutter" to make his case in the new dispute, which was brought by conservative activists who had in past cases enlisted White student plaintiffs and this time sued on behalf of Asian American students.

Roberts and Sotomayor more passionately differed, however, over how race informs an individual's identity.

For too long, Roberts said Thursday, universities have categorized students based on the color of their skin and presumed that members of a distinct minority group share similar views.

"And in doing so," he wrote, "they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual's identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin."

Sotomayor rejoined that Roberts was turning away from "uncomfortable truths" and being blind to the reality of how much racial attitudes and discrimination permeate the country.

"(B)ecause the Court cannot escape the inevitable truth that race matters in students' lives," Sotomayor wrote, "it announces a false promise to save face and appear attuned to reality. No one is fooled."