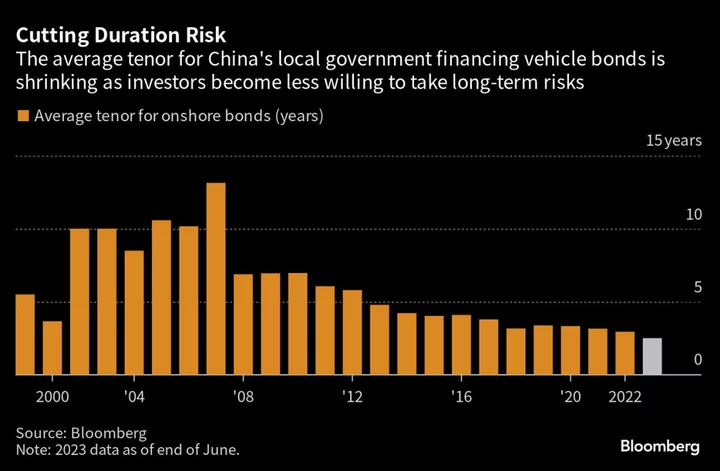

Investors in China’s local government financing vehicles are cutting the length of time they are prepared to extend credit and demanding higher returns, as cracks appear in the $9.1 trillion market.

In the first half of 2023 the average tenor — the length of time before a debt matures — of onshore LGFV bond issuance fell to 2.51 years according to Bloomberg calculations. That’s down from 2.95 years in 2022 and the shortest since at least 1999 when the data series began.

Additionally, the average coupon on LGFV yuan bonds jumped to 4.39% in the first six months of the year from 3.94% last year despite the fact that China is easing monetary policy.

In another warning signal, China’s state pension fund, one of the country’s biggest investors, has advised asset managers that handle its money to sell some bonds including those from riskier LGFVs and private developers after a review, Bloomberg News reported Wednesday.

This increased investor caution points to looming refinancing challenges for a sector considered China’s top financial stability risk. If provinces are only able to refinance at less favorable rates, that may force them to scale back spending, dragging on China’s already spluttering economy. Moreover, if any were to miss these new higher payments, that could force a rapid repricing of credit and send borrowing costs soaring to unaffordable levels.

“Heavily relying on shorter-tenor bonds for financing will make these regions’ ability to refinance even more fragile,” said Zhao Guojun, credit analysis director at the fixed income department of Wanlian Securities Co. “If market sentiment weakens, there may be liquidity risks or technical defaults.”

Focus of Concern

While no LGFV has yet defaulted on a public bond, the majority of regional governments face a severe funding crunch. The property slump has slashed income from land sales while public spending jumped during the pandemic. Half of cities experienced difficulty in managing debt interest payments last year, Rhodium Group said.

The new, more cautious, funding environment is particularly tough for weaker regions.

Take Qinghai, a sparsely populated western province. Its funding costs hit 7.1% this year, compared to just 3% for financial hub Shanghai, Bloomberg’s calculations show. Tianjin, a manufacturing center known for over-development, saw its average coupon jump nearly a percentage point in the first half of 2023.

As well as higher costs, it’s these same regions that also have to borrow on shorter terms.

“It is hard for LGFV issuers to issue long-dated bonds, especially those in weaker areas,” said Janet Lu, head of fixed income China, Eastspring Investment Management (Shanghai) Co. “There’s also uncertainty on how the government policy in handling LGFV debt will evolve in the longer term.”

In a reflection of the difficulties in rolling over debt, overall net refinancing fell 6.5% in the first half of the year. That could force LGFVs to turn to other channels to fill their funding gaps — and these are getting harder to find. Chinese banks recently stopped buying a type of debt called “free-trade-zone bonds” where LGFVs were the major issuers.

Intervention Watch

The underlying problem is most infrastructure projects built by LGFVs never generated enough money to cover their debts, relying instead on cash injections from local government and refinancing to stay afloat.

While LGFV bonds are classed as corporate debt, investors generally assume they are backed by an implicit government guarantee. LGFVs had about 13.5 trillion yuan of outstanding onshore bonds at the end of 2022, according to data from S&P Global Ratings — representing about 40% of China’s non-financial corporate bond market.

The vast majority of that debt is held by domestic investors, spanning all types of financial institutions from commercial banks to insurers and mutual funds. That means any problems could ripple through the whole financial ecosystem.

Already there are concerns that banks may incur losses after some state-owned lenders started to offer additional credit support. Banks including Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. and China Construction Bank Corp. are offering loans that mature in 25 years, instead of the prevailing 10-year tenor for most corporate lending, people familiar with the matter told Bloomberg in July.

Despite all of these issues, there is still no panic in the market. Key spreads between yuan-denominated LGFV bonds and similar-maturity sovereign debt even narrowed earlier this year.

That’s partly because while the recent last-minute payment of a note raised concerns about the sector’s debt-servicing abilities, even struggling regions appear to be prioritizing timely bond payments.

“On a positive note, we have seen consistently strong support from local governments to these platforms to ensure timely repayment of bonds which we expect to continue at least in the short term,” said Eastspring’s Lu.

Despite the central government’s attempts to discourage the idea it will bail out the sector if things go wrong, most investors fundamentally don’t believe it. Options for possible targeted intervention include the establishment of debt service funds to provide liquidity to weaker platforms or extending financing channels through state-owned companies.

“The market is now expecting some policy measures from the central government,”said Moody’s Investors Service Associate Managing Director Ivan Chung. “If any of these debt problems leads to systemic risks or undermines social and economic stability, I think the central government will step in.”

Data from 2022 onwards are calculated based on LGFV bonds issued by the end of 2021, on the assumption that LGFVs that have been set up since then don’t impact the data significantly.

--With assistance from Ailing Tan, Yoshihiro Sato and Kevin Zhang.

(Updates with comments and other details)