As Europe seeks to exit fossil fuels, a relatively unproven alternative is forming the backbone of its clean-energy plans — but failing to convince investors.

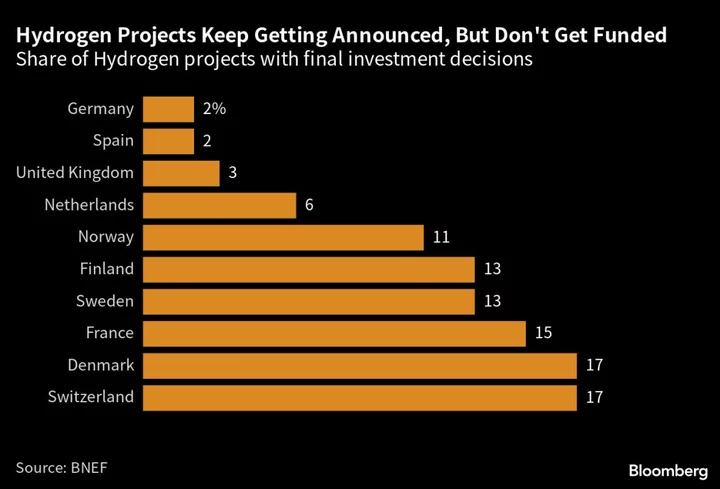

Hundreds of hydrogen projects have been floated by governments in the past years, yet only 7% of those have the financing to start construction, according to data compiled by Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

That highlights the prevailing skepticism over the ability to produce large amounts economically, and contrasts with the situation in the US, where generous subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act are luring investments for renewables including hydrogen.

The gas is made by splitting water with electricity, and can be burned to create energy without releasing carbon dioxide. It has the potential to use existing gas networks to bring fuel to heat homes — a big advantage for governments whose finances are stretched after years of crisis firefighting — while complementing the intermittency of renewables.

“The hydrogen sector is now getting a lot of hype,” said Adithya Bhashyam, a hydrogen analyst at BloombergNEF. “There’s a lot of project activity in terms of announcements and very little is actually being built.”

Energy companies say there’s not nearly enough infrastructure in place to use hydrogen as a fuel for power plants or transport it to end users, making it complicated to plan large-scale investments. Even the hundreds of projects that have been proposed only have the capacity to provide about 3.5% of the European Union’s projected energy needs by 2030.

Governments are steering their economies out of the worst energy crisis in decades with policies to guarantee domestic supply and limit damage to the environment. Many are counting on hydrogen to replace fossil fuels where other renewables — such as wind and solar — are unable to, because certain industrial processes can’t easily be electrified.

Hydrogen’s main advantage is that it’s a way to store excess power produced by wind farms at sea and solar parks in distant deserts for future use. It can also be made using low-carbon technologies, boosting its attractiveness for governments that are trying to exit coal. UK Energy Secretary Grant Shapps, for instance, aims to produce enough hydrogen by 2030 to power London for a year.

But companies in Europe’s energy sector say an expansion at such a fast pace requires greater regulatory clarity, as well as financing from governments.

“The legislative details aren’t there yet,” according to Marco Alvera, Chief Executive Officer of Tree Energy Solutions, a Belgian company that builds large-scale hydrogen projects. He says officials should support manufacturing of electrolyzers — expensive machines that split molecules to produce hydrogen — and create special contracts that incentivize the use of renewables in powering them.

While some support measures are already underway — including a €3 billion ($3.2 billion) investment vehicle, known as a hydrogen bank, dedicated to building a future market for the fuel — European Union regulations for production won’t come into full force until 2028.

Struggling Economics

Another issue is the technology’s early research stage. Even German utility EnBW Energie Baden-Württemberg AG, which has the country’s most advanced plans to switch plants and run them on hydrogen, still has doubts about the outlook.

“There’s a lot to be learned and it will take a while before we can really talk about economics here,” EnBW Chief Financial Officer Thomas Kusterer said on a recent call to analysts.

Hurdles emerge even before hydrogen molecules reach the network. Hydrogen is the lightest and smallest element, and in its liquid form can be explosive when exposed to air. That makes it difficult to transport and requires building appropriate infrastructure.

Some gas grids can be used to transport hydrogen, though existing ones are often too leaky. While EnBW said it will be able to run some of its gas plants with 75% hydrogen, Kusterer added that the current grid in Germany can only transport 20%.

The EU’s plan to both produce and import 10 million tons of hydrogen by 2030 seems so far to be a distant hope.

Political wrangling is stalling progress on a multibillion-euro pipeline that policymakers hope will eventually pump fuel from Barcelona to Marseille and Berlin. Converting liquefied natural gas terminals — such as those newly built in Germany — to allow imports by ship is likely to be costly.

But challenges in producing or obtaining the fuel form only a part of energy companies’ concerns. What’s more worrying to them is who will eventually buy it.

“There’s no point producing huge volumes of hydrogen if you don’t have off takers who are ready to actually use that hydrogen,” said Brett Ryan, head of policy and analysis at trade association Hydrogen UK.

--With assistance from William Mathis.

(Updates with US context in third paragraph.)