It wasn't until after Army Capt. Larry Taylor had picked up four of his fellow soldiers during a raging firefight in Vietnam -- the men clinging onto the outside of his helicopter, as there wasn't room inside -- that he realized he had to figure out where to take them.

It was June 18, 1968, and then-1st Lt. Taylor and his copilot had been called out in their AH-1G Cobra helicopter to rescue a four-man long-range reconnaissance patrol team who were pinned down by the enemy, with seemingly no way out.

"My copilot says, 'Sir, now that we've got 'em, what the hell are we going to do with them?'" Taylor recounted to reporters last week. "I said, I don't know, I didn't think that far ahead."

In a matter of moments, Taylor decided to drop them at a nearby water treatment plant where other Americans were waiting on the ground.

"We took them down there and I landed, and I left my wide landing lights on and so the four of them ran out in front of the helicopter and then they turned around and lined up, all four of them, saluted, and then ran for the lights," Taylor said.

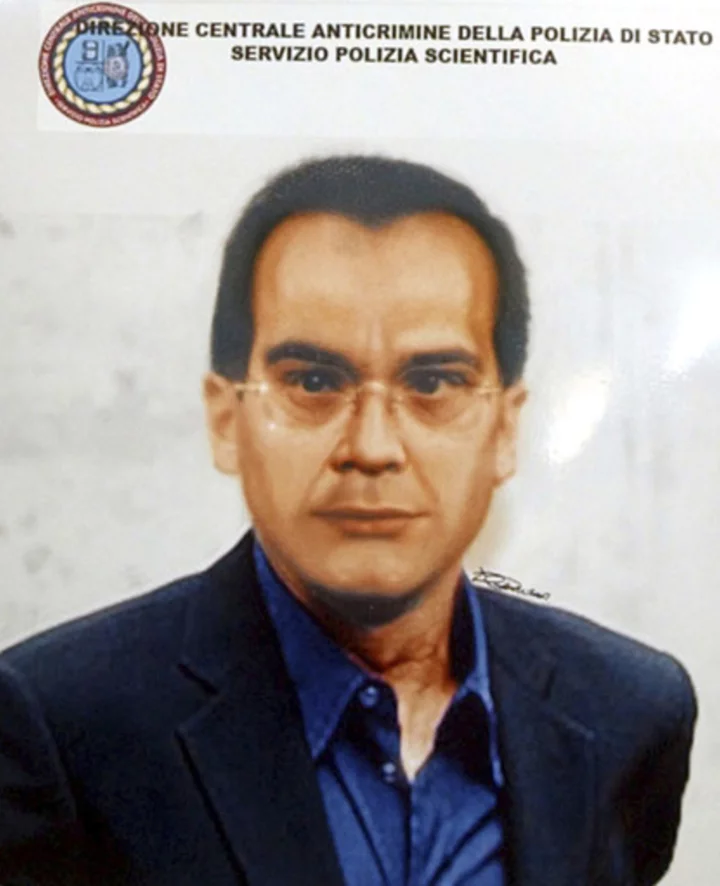

Now, 55 years after that harrowing evening in Vietnam, Taylor will receive the Medal of Honor -- the nation's highest military award -- from President Joe Biden on Tuesday at the White House for his heroism.

"Taylor's conspicuous gallantry, his profound concern for his fellow soldiers, and his intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army," a White House news release said last week.

But for Taylor, who received dozens of combat awards and flew over 2,000 combat missions during his time in the military, his actions that night in 1968 weren't anything particularly special.

"I was doing my job," he said matter-of-factly. "And I knew that if I didn't go down and get them, they wouldn't like it."

'And the fight was on'

Taylor, born in Tennessee in 1942, joined the Army Reserve Officer Training Program while attending the University of Tennessee. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army Reserve in June 1966, according to his biography, and joined the active-duty Army in August that year as an armor officer.

It wasn't long before Taylor realized he'd rather be an aviation officer than an armor officer -- partly because of what was unfolding in Vietnam. If the option was between being on the ground, where troops were being bombarded with gunfire and mortars constantly, or in the sky with rockets and thousands of rounds of ammunition, the choice was clear.

"You can kick some ass," Taylor said of being in the Cobra. "So, yeah, I'd rather be an ass-kicker than to have my ass kicked."

Taylor's biography says that throughout his 2,000 combat missions in UH-1 and Cobra helicopters, he was forced down five times and engaged by enemy fire 340 times. He earned at least 50 combat decorations -- by his count, around 60 -- including 43 Air Medals, a Bronze Star, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, and the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Bronze Star.

David Hill, who was one of the soldiers Taylor rescued, explained that on the night of Taylor's heroic actions, he and his three teammates had been assigned an area reconnaissance mission. Typically, Hill said, they would have been inserted into the jungle by helicopter, but this was "an entirely flat rice paddy area."

Being dropped in by helicopter would have blown their mission, he said, so instead they walked. The goal was to observe any enemy troop movements, so when the evening was almost completely dark, Hill said they walked out of the wood line to set up their position. But before they could, they were surrounded by enemy troops.

"The plan changed, and now was a matter of not escaping but having to fight it out right there," Hill said.

As the four-man team was preparing to fight, they were simultaneously calling back to the forward operating base for help. The call went out for air support -- and Taylor answered. Within two minutes, Hill said, Taylor and his co-pilot had strapped in and taken off, heading towards Hill and his men.

Taylor explained that from his perspective, the night was so dark he wasn't sure he'd be able to find the troops on the ground. He used his radio to coordinate the rescue, telling the men on the ground to drop flares to help guide him in. As soon as they popped the flares, Hill recalled, "all hell broke loose."

"Obviously we gave away our position, but we knew we would be discovered at some point anyway because we were surrounded," Hill said. "And the fight was on."

The White House announcement describes how Taylor and his wingman "strafed the enemy with mini-guns and aerial rockets," and "continued to make low-level attack runs for the next 45 minutes." He learned that the rescue attempt by another helicopter had been canceled, according to the White House release, because "it stood almost no chance of success."

So Taylor decided to do it himself with his two-man Cobra helicopter -- "a feat that had never been accomplished or even attempted."

Taylor told reporters that as soon as a soldier on the ground radioed up that his helicopter was over their position, he "plopped it on the ground."

"I didn't have to tell them to get on," he said. But the helicopters size -- a two-person aircraft -- meant the soldiers would have to secure themselves to the outside.

"I finally flew up behind them and sat down on the ground, and they turned around and jumped on the aircraft -- a couple were sitting on the skids, one was sitting on the rocket pods, and I don't know where the other one was but they beat on the side of the ship twice, which meant, 'Haul ass,'" Taylor said. "And we did."

In retrospect, Taylor said they were all coming up with what to do next on the fly. There's "nothing in the book that says how to do that," he said.

"I think about 90% of flying a helicopter in Vietnam was making it up as you go along," he said. "Nobody could criticize you because they couldn't do it any better than you did and they didn't know what you were doing anyway."

But it must have worked, he added, because throughout his thousands of combat missions, "we never lost a man."