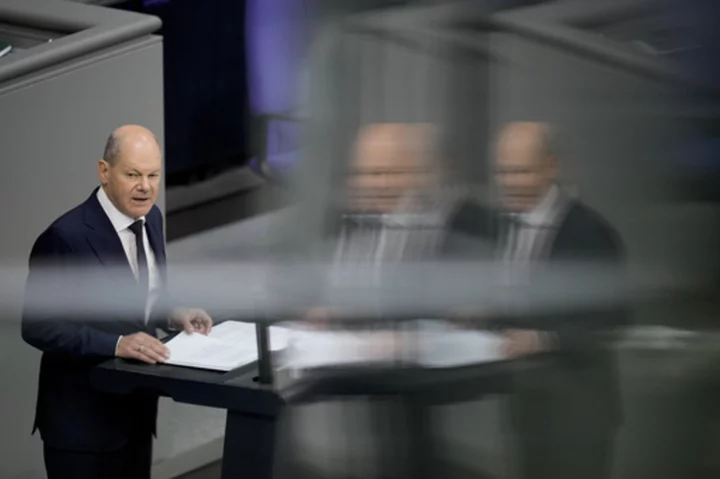

BERLIN (AP) — German Chancellor Olaf Scholz on Thursday defended a deal to stop migrants from entering the European Union until their chances of getting asylum have been reviewed, arguing that the bloc's existing arrangement is “completely dysfunctional.”

Speaking to lawmakers in Berlin, he said the compromise reached earlier this month by the EU's 27 member states after years of negotiations was a “historic agreement.”

Human rights groups have criticized the deal, saying migrants, including families with children, will be held in camps while authorities check whether they are likely to be granted refugee protection inside the EU. The details are still to be worked out in negotiations with the European Parliament, which must approve the change to EU migration rules.

“I know that the agreement isn't without controversy in this house,” Scholz told parliament. “Everyone had to make compromises, including Germany.”

“But it was the right thing to do in the interest of Europe's unity and ability to act,” he added. “It was right, because our current system is completely dysfunctional.”

In the period from January to May, a total of 135,961 people applied for asylum in Germany, up 76.6% on with the same period last year, according to the country’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees.

Most of them came from Syria, Afghanistan or Turkey.

In 2022, 12,945 rejected asylum seekers were deported from Germany. However, according to German authorities, there were 304,308 people in Germany as of December 31, 2022, whose asylum plea had been rejected but who have not yet been deported, German news agency dpa reported.

The reasons for the delay in deporting them are manifold, running from health issues to bureaucratic hurdles. It often takes years until a final decision on an asylum application has been made because applicants can appeal through the courts if their claim is turned down.

Scholz noted that many migrants don't apply for asylum until they reach Germany, even though the country is surrounded by other EU member states that would have had to register them first under the bloc's existing rules.

“Those who only have a very slim chance of being recognized as refugees will go through a swift asylum and return process at the (EU's) external borders in the future,” he said. “Those who have good chances of getting protection in Europe, however, because they come from war zones or are politically persecuted, will be registered and able to enter the EU in the future.”

Scholz said the new system would ease the burden on Germany, which has seen more than 2 million asylum applications over the past decade.

He stressed that countries which refuse to take in their share of refugees would in future have to make a financial contribution toward the cost borne by others.