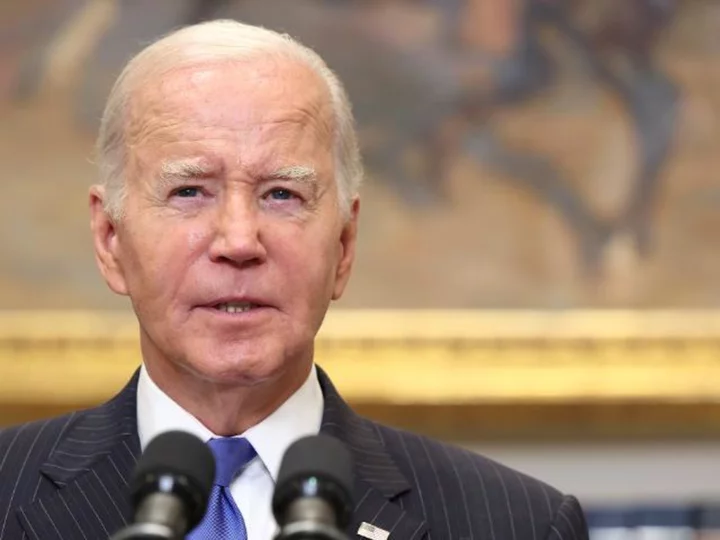

With the outbreak of war in Israel, President Joe Biden is contending with conflicts in two parts of the world at a moment of paralysis in Washington and increasing polarization over the direction of America's involvement abroad.

The moment is exactly the type of global crisis Biden pledged to voters he was uniquely prepared to confront, particularly when compared with his predecessor. Spending almost 50 years in proximity to the American foreign policy establishment gives Biden a perspective shared by few, if any, in Washington.

But this is also a major test of his ability to corral alliances at home and abroad behind American leadership, all while dysfunction in Washington undercuts some of his authority and competing world powers jockey for influence.

Biden vowed within hours of Hamas' attack on Saturday that his administration's support for Israel's security was "rock solid and unwavering." In a Sunday conversation with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Biden said that assistance was "on its way," with additional help forthcoming.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin announced Sunday that a US carrier strike group is headed to the eastern Mediterranean Sea as a "deterrence posture." In his statement, Austin also said the US "will be rapidly providing the Israel Defense Forces with additional equipment and resources" and noted that these decisions followed "detailed discussions with President Biden."

Still, delivering on Israel's request for additional support is not an uncomplicated undertaking for Biden.

With the war in Ukraine now well into its second year with no apparent end in sight, recent polling has shown that the American public's support for supplying Ukraine with more weapons is starting to fray. A Reuters/Ipsos poll conducted earlier this month showed 41% of respondents agreed with the statement that Washington "should provide weapons to Ukraine" -- down from 46% in May.

Before Saturday's stunning attack on Israel, the White House was already grappling with how to move additional funds for Ukraine through a divided Congress, after hardline Republicans managed to strip billions of dollars in Ukraine assistance from a government funding bill. At the start of the war, support for Ukraine was more widespread.

And the emergency situation in Israel comes as the House is in a state of paralysis -- and uncharted legal territory -- without an elected speaker after Kevin McCarthy's historic ouster last week.

Aid for Israel will likely be a different proposition from Ukraine assistance, and there was widespread bipartisan condemnation of the Hamas attack among lawmakers on Saturday, including those to Biden's left who have sometimes adopted different views toward Israel.

Among the likely asks of the US by Israel will be additional interceptors for its Iron Dome missile defense system, an official said.

Yet those same strains of resistance on Capitol Hill will still confront Biden if his administration pursues a new aid package for Israel.

"I look at the world and all of the threats that are out there, and what kind of message are we sending to our adversaries when we can't govern? When we're dysfunctional? When we don't even have a speaker of the House?" House Foreign Affairs Chairman Michael McCaul, a Texas Republican, said Sunday on CNN's "State of the Union."

By all accounts, the sudden explosion of violence in Israel came as a surprise to Biden and his aides. It was just over a week ago that Biden's national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, told an interviewer, "The Middle East region is quieter today than it has been in two decades" -- a statement that at the time was largely true.

He did go on to note that "all of that can change," and senior administration officials have emphasized that rising tensions in Gaza and the West Bank have been a concern for months.

That is partly why Biden was hopeful he could broker an agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia to establish diplomatic ties, a historic undertaking that US officials said could bring a new degree of stability to the Middle East.

Administration officials refused to close the door on those efforts this weekend, even as they acknowledged the diplomacy was now infinitely more complicated. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Sunday that part of the rationale for the Hamas attacks might have been to disrupt the normalization talks.

"That could have been part of the motivation," he told Dana Bash on "State of the Union."

Still, Sullivan's comments underscored a widely held view within the administration that the Middle East was no longer occupying the central role it once did in American foreign policy.

That view wasn't necessarily unique to Biden's team. The past three administrations have sought to refocus American foreign policy to Asia, hoping to challenge China's rise. Even former President Donald Trump, who successfully brokered diplomatic agreements between Israel and some Arab nations, was more focused on trade deals with Beijing and summits with North Korea.

Biden made returning the United States as a relevant global power central to his campaign after the years of Trump's "America first" agenda. He used his long experience in the arena as a selling point. On Israel in particular, he has frequently pointed to his decadeslong relationship with Netanyahu as key to his understanding of the Israeli leader, even as their ties have come under recent strain.

The sudden onset of the war in Israel stood in stark contrast to the beginning of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which the US warned about for months ahead of time using downgraded intelligence.

Even for a president as long immersed in American foreign policy as Biden, a ground war in Europe was not likely among his top foreign policy fears. A conflict in the Middle East -- despite the relative calm of the last years -- would have seemed more likely when Biden entered office.

In any case, wars in both places are on his plate.

And there's now an additional challenge: a House of Representatives that does not have a permanent speaker. The acting speaker, Rep. Patrick McHenry, does not have the full authority of a permanent speaker, raising the prospect that the lower chamber may be paralyzed until the next speaker is in place.

As Biden's aides were huddling at the White House on Saturday trying to determine the scope of Israel's needs, the question arose over Congress' ability to pass new assistance without a speaker. They did not arrive at an answer.

A senior official acknowledged that the situation was entirely "unique" and that administration officials were attempting to discern what was achievable.