Russia's short-lived insurrection has handed Joe Biden the most perilous version yet of a dilemma that has confounded the last five US presidents: how to handle Vladimir Putin.

Every US commander in chief since Bill Clinton has sought in some way to engage the former KGB officer, whose mission to restore Russian greatness was ignited by his humiliation at the fall of the former Soviet Union. Most have sought some kind of reset of US-Russia relations. But all failed to avert the plunge in ties between the two nuclear superpowers.

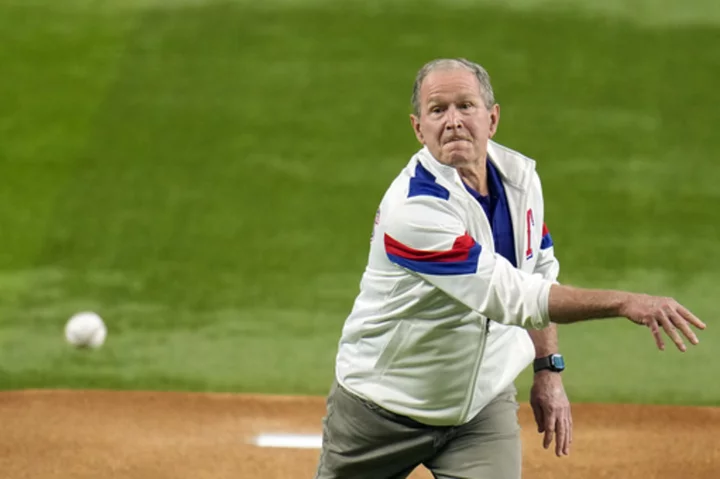

Ex-President George W. Bush looked into Putin's eyes and got "a sense" of his soul, only for Putin to invade Georgia on his watch. Barack Obama initially saw the Russian leader as a partner in a drive to end the threat of nuclear Armageddon. That didn't stop Putin from annexing Crimea in 2014. And Donald Trump adopted a fawning approach to an autocrat and US foe he often seemed to want to emulate more than condemn.

Biden, who came of age in Washington as a senator during some of the most embittered years of the US-Soviet standoff in the 1970s and 1980s, had fewer illusions about Putin than most. But even he tried to break the chill, by meeting his counterpart at a summit in Geneva in 2021.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine, however, led him instead to reinvigorate the NATO alliance with an extraordinary pipeline of arms and ammunition designed to ensure the country's survival. Western support has not only enabled Ukraine to fight back against invading forces, it has helped turn the war into a quagmire that spiked political pressure on Putin and created battlefield conditions that likely helped lead to mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin's revolt over the weekend.

Putin appeared on camera on Monday, defiantly warning that he would have had no trouble suppressing the uprising had the Wagner Group leader not chosen to halt his march on Moscow in a deal that ostensibly will see him exiled to Belarus.

But there was widespread agreement outside Russia that the showdown represented the most serious challenge to Putin's grip on power during his generation in control and could even be a crack that spells the beginning of the end of his authority.

So Biden, therefore, faces a possibility that none of the predecessors who wrestled with Putin had to contemplate -- that he is dealing with the endgame of this modern czar, and the prospect of instability rocking a nuclear superpower that could have global implications.

Avoiding escalation

During the chaos that engulfed Russia this weekend, the US and its allies made clear that the eventually aborted showdown between Putin and Prigozhin was an internal Russian affair. After Moscow opened a propaganda front on Monday by claiming it was probing whether Western intelligence was involved in the coup attempt, Biden went out of his way to dismiss the idea, discussing how he had consulted with Western leaders on the right approach.

"They agreed with me that we had to make sure we gave Putin no excuse. Let me emphasize, we gave Putin no excuse to blame this on the West or to blame this on NATO. We made clear that we were not involved. We had nothing to do with it," the president told reporters.

CNN reported Monday that the US had warning of Prigozhin's intentions in advance, but only shared it with select senior officials and allies, including the British. The revelation appeared to be the latest indication that the US is getting high-grade, accurate intelligence from inside Russia, as it appears to have done for the last year. This in itself must be deeply irksome to Putin and may deepen his bunker mentality.

Biden's comments, meanwhile, also reflected the odd dichotomy of his strategy toward Putin. While sending Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky billions of dollars in arms and ammunition to fight for his country's survival, Biden has simultaneously insisted that the US is not involved in a showdown with Russia, doing everything he can to avoid a direct clash between NATO and Russian forces that could risk a world war-style escalation.

But the red lines have been constantly expanding. The stocks of ammunition, heavy artillery, Patriot anti-missile missiles and tanks that have been flowing into Ukraine would have been considered unthinkable when Putin ordered his troops over the border last February.

Still, Biden's insistence that there was no US involvement in the weekend rebellion is almost certainly a statement of fact. The US has no dog in a fight between a warlord like Prigozhin, whose guns for hire are accused of a catalog of atrocities in Ukraine and Syria, and a Russian leader who is the subject of an arrest warrant for war crimes.

Moscow's claims that the West was complicit in the uprising come across as a diversion from splits threatening to erode Putin's rule. They appear designed to convince Russians to unite against an outside enemy. Putin has repeatedly styled the war in Ukraine as a struggle against what he sees as a Western effort to deny Russia its rightful status as a global power. This is a distraction from the fact he sent his troops into Ukraine in contravention of international law, sparking a conflict that has exposed the supposedly mighty Russian army as poorly led and equipped -- a shell of the Red Army that upheld the Soviet Empire.

An evolving Western response

While the US and its allies took care not to show triumphalism while Prigozhin's rebellion was taking place, Western governments are now seeking to capitalize on it politically, as they try to build pressure on Putin inside Russia.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken argued on America's Sunday talk shows that while the US was not involved in the rebellion, it showed cracks in Putin's power. This was a refrain taken up in Europe on Monday.

"Prigozhin's rebellion is an unprecedented challenge to President Putin's authority, and it is clear that cracks are emerging in the Russian support for the war," British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly said. European Union High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell adopted a similar line, after several days of consultation between top officials in the Western alliance. He said events show Russia's military power "is cracking," adding that the instability is also "affecting [Russia's] political system."

Some experienced American observers have warned that it is far too soon to write Putin off.

"This struck me as a desperation by Prigozhin to somehow keep the Wagner Group in operation. I don't see it as a populist threat to Putin, I don't see it as cracking the aura of Putin's invincibility," former Trump national security adviser John Bolton told CNN Monday, though he did allow that Putin's military position is "undeniably" weakened.

Putin has shown no sign that outside heat from Moscow's foes will force him to retreat and bring his troops home. Indeed, his position may be so vulnerable that doing so without gains he could pass off publicly as a victory could pose an existential threat to his leadership. This explains why thousands of Russian troops have been sent into a "meat grinder" of a conflict, as Prigozhin called the battle in Bakhmut, that has shattered Russian prestige and worsened its strategic position in Europe.

But with the war going poorly in Ukraine, Putin is now facing a new political front at home after his personality cult of an all-powerful autocrat impervious to challenge was punctured by Prigozhin.

Unless the Russian leader can reestablish his authority, Biden may end up being the first 21st century American president who ends up outmaneuvering the strongman in the Kremlin.