The racist motivations of the white shooter who targeted and fatally shot Black people in Jacksonville, Florida, two weeks ago have revived concerns about the threat of hate violence and domestic terrorism against African Americans.

Most hate crime victims in the U.S. are Black, and that has been the case since the federal government began tracking such crimes decades ago. But national attention on the rate of Black victimization is heightened in the wake of mass casualty racist attacks, like those in recent years at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, and a historic Black church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Now, as families in Jacksonville eulogize loved ones lost in a hail of bullets at a neighborhood discount store, activists across the nation are calling for better measures to counter the longstanding epidemic of hate violence against Black Americans.

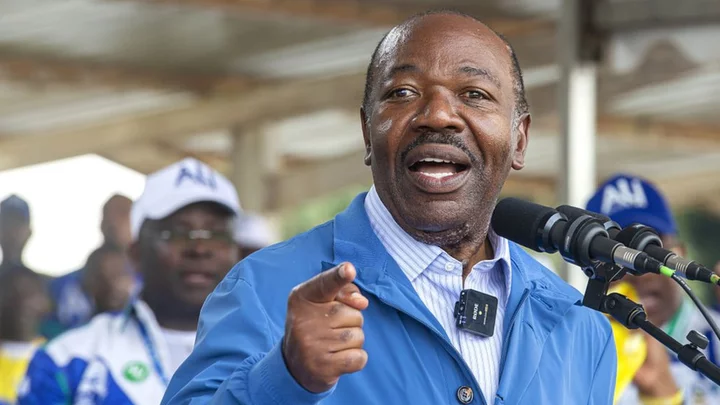

“How many people have to die, before you get up, whether you’re Republican or Democrat, and say we got to stop this,” the Rev. Al Sharpton asked Friday as he eulogized Angela Carr, one of the victims of the gunman who shot down three Black people at a Dollar General store in Jacksonville on Aug. 26.

Funerals were held in Florida for two of the three victims on Friday, with the third planned for Saturday.

Sharpton pointed to reports of neo-Nazi demonstrations in Orlando, seen just days after the Jacksonville shooting, as evidence that a climate of hate has been fomented in Florida and across the U.S.

“Look at the data,” he said.

Anti-Black hate crimes peaked in 1996 at 42% of all hate crimes, then began a steady decline until 2020. June of that year was the worst month for anti-Black hate crimes since national record-keeping by the FBI began.

Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, cautions that there are gaps in the agency’s reports that can present a misleading picture of hate crimes in parts of the country. Florida, along with Virginia, Mississippi and Arkansas, had the lowest reporting rates of hate crimes to the FBI in 2021.

“We generally see increases in hate crimes in election years and around catalytic events,” said Levin. “We’re talking about almost 500 to 700 more hate crimes in an election year. Politics seems to be a catalyst.”

Levin said there is substantial underreporting. Even with the FBI’s revised reporting for 2021, the rate only captured 80% participation, he said.

“Imagine if we had even more,” he said.

In 1990, Congress passed legislation that required the Justice Department to collect data on crimes motivated by race, religion, sexual orientation and ethnicity. The FBI does the data collecting through the Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

But after years of collection, the problem of hate-motivated violence has increased over the last decade. The number of hate crimes in the U.S. jumped up in 2021 from an already alarming increase in the previous year, according to FBI data released in March.

Among the 2021 victims, 64.5% were targeted due to their race, ethnicity or ancestry. Another 16% were targeted over their sexual orientation, and 14% of cases involved religious bias.

On Friday, leaders from more than 30 national civil rights organizations sent a letter to the White House requesting a meeting with the Biden administration to address hate-motivated violence. If convened, it would be the first such gathering since a “United We Stand” summit with the president and administration officials in September 2022.

This time, the groups said they want to discuss steps that federal agencies other than the Justice Department could take to increase awareness of hate crimes and identify ways communities can respond to hate and violent white supremacy. They also requested a report detailing the administration’s progress since last year’s summit.

“As we approach the one-year anniversary of this summit, the latest mass hate crime — in which three Black people were murdered at a store in Jacksonville, Florida — serves as a stark reminder of the repeated devastation that hate has on communities across the country,” reads the letter signed by organizations such as The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Inc. and the Anti-Defamation League.

“Our communities are facing an unprecedented threat from the hate-filled forces that seek to divide our nation,” the group wrote.

It was unclear Friday if the White House received or responded to the letter.

President Joe Biden spoke to reporters about the Jacksonville shooting last week, while he and first lady Jill Biden were in Florida surveying the aftermath of Hurricane Idalia.

“We’re still reeling from the shooting rampage, a terrorist attack driven by racial hatred and animus,” Biden said. “Let me say this clearly: Hate will not prevail in America. Racism will not prevail in America. Domestic terrorism will not prevail in America.”

In 2021, Biden signed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act to address the spike in anti-Asian hate crimes seen at the height of the coronavirus pandemic. Some advocates lament the lack of legislation specifically addressing the high rate of Black victimization, while others point to progress like the enactment of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act last year. The law makes lynching a federal hate crime.

While it is the deadly, high-profile hate crimes, like the shooting at the Buffalo supermarket that killed 10 people last year, that get a lot of attention, there are far more incidents that never make national news. Use of the N-word on some social media websites spiked in the summer of 2020, just as social justice protests took place around the country in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by police in Minneapolis.

Damon Hewitt, president and executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, said his organization examines the toll violent hate has on Black people and other communities of color. Shortly before the pandemic, it launched the James Byrd Jr. Center to Stop Hate to support victims of hate incidents and destabilize white supremacist organizations and their infrastructures.

The center is named in recognition of Byrd, the Black man who was dragged to death by white supremacists 25 years ago in Jasper, Texas. Byrd’s death is viewed as one of the most gruesome hate crimes in U.S. history.

“We also want to discredit not only their tactics but also their ideology, which we think is very important, because silence is the cousin of complicity,” Hewitt said.

Many have noted how Black people seem to be encountering hate incidents while conducting everyday tasks such as jogging, grocery shopping or attending class on a college campus.

“We’re not safe anywhere,” Hewitt said. “So how can we have peace of mind? How can we pursue an American dream when America is always pursuing us?”

During a Thursday virtual press conference that referenced the Jacksonville shootings, the Rev. William Barber II, president of Repairers of the Breach, warned against hateful political rhetoric that he said fostered an environment for such an attack. He called out public officials “who are using the words of culture wars to attack Black history, to attack Black people,” specifically naming Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has overseen several laws and policies that restrict the teaching of race in schools.

Barber said there was a “through line in history” of divisive rhetoric and hate, connecting policies and laws targeting Black people in the U.S. to incidents of violence in the last century.

“The power of life and death is in the tongue,” he said.

DeSantis, a Republican candidate for president, has rejected suggestions that he did not condemn the Jacksonville shooting in the strongest terms and that he has more broadly ignored the concerns of Florida’s Black community.

Sharpton said he attended Friday's funeral to be there for the victims’ families and to not allow the media to so quickly move on from the tragedy.

“There’s something that bothers me, that for two days maybe, the national media talked about Angela (Carr) and talked about the other two, and then went on to something else like their lives meant nothing,” Sharpton said.

“I don’t want you to feel this is a two-day story,” he said. “This is a 400-year story.”

__

Jefferson reported from Chicago. Morrison and Nasir, who both reported from New York, are members of the AP’s Race and Ethnicity team.