WASHINGTON (AP) — An inflation index that is closely monitored by the Federal Reserve tumbled last month to its lowest level since April 2021, pulled down by lower gas prices and slower-rising food costs.

At the same time, consumers barely increased their spending last month, boosting it just 0.1%, after a solid 0.6% gain in April.

The inflation index showed that prices rose 3.8% in May from 12 months earlier, down sharply from a 4.4% year-over-year surge in April. And from April to May, prices ticked up just 0.1%.

Still, last month's progress in easing overall inflation was tempered by an elevated reading of “core” prices, a category that excludes volatile food and energy costs. The increase underscored the Fed's belief that it will need to keep raising interest rates to conquer high inflation.

Core prices rose 4.6% in May from a year earlier, down slightly from the annual increase of 4.7% in April. It was the fifth straight month that the core figure was either 4.6% or 4.7% — a sign that the Fed’s streak of 10 rate hikes over the past 15 months hasn’t subdued all categories of prices. From April to May, core prices increased 0.3%, a pace that, if it lasts, would keep inflation well above the Fed’s 2% target.

Friday's report from the government suggested that consumer spending is slowing under pressure from high prices and interest rates, a trend that is also likely cooling inflation. As a result, many economists think growth in the current April-June quarter will slow from the 2% annual pace in the first three months of the year.

That cooldown could lead the Fed to decide to skip a rate hike when it meets in September, after a widely expected increase at its next meeting in late July.

“The stickiness of core inflation continues to be the proverbial bee in the bonnet of policymakers at the Fed,” said Shernette McLeod, an economist at TD, a bank. “Consumers continue to be a pillar of support for the U.S. economy. Nevertheless, they are coming under increasing pressures, with high prices, tightening credit and other indicators pointing to a slowdown on the way.”

Grocery prices edged up just 0.1% from April to May, providing some relief to consumers, though food costs are still 5.8% higher than they were a year ago. Gas prices, which sank 5.6% just from April to May, have plunged 22% over the past year.

Used cars soared 4.7% from April to May, though they're still 2.2% cheaper than they were a year ago. Economists expect used car prices to fall soon because measures of wholesale used car costs are declining.

Housing costs keep rising and fueling overall inflation, with rents increasing 0.5% from April to May and 8.7% over the past year.

Friday's report also showed that Americans' incomes rose a solid 0.4% from April to May, outpacing inflation and providing more fuel for future spending.

The report arrives two days after Chair Jerome Powell said the Fed was prepared to keep interest rates at their peak for an extended period to tame the still-rising prices that have shrunk Americans' inflation-adjusted paychecks and disrupted businesses. The Fed's policymakers, as a group, envision two additional rate hikes this year.

“The bottom line is that (interest rate) policy hasn’t been restrictive enough for long enough,” Powell said in his remarks at an international forum in Sintra, Portugal. He reiterated his view that prices for services, such as restaurant meals, hotel rooms and health care, are still rising too fast, driven in part by the need of many companies to raise pay to attract and keep workers.

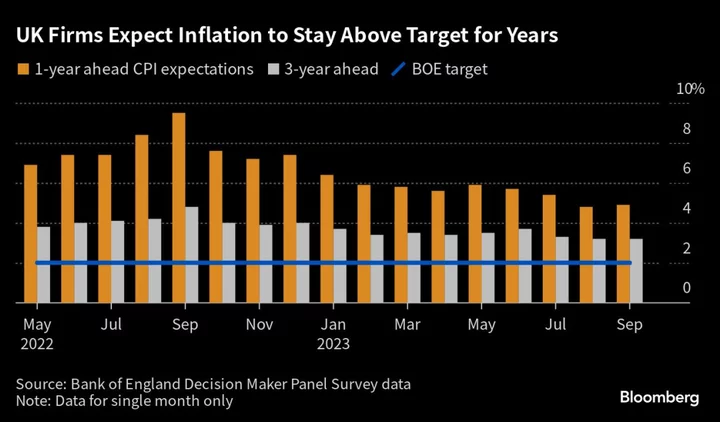

Inflation has also eased in the 20 countries that use the euro, according to a separate report released Friday. Prices rose 5.5% in June compared with a year ago, down from 6.1% in May. But as in the United States, core inflation has proved more stubborn: It ticked up from 5.3% to 5.4%.

European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde and Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey, along with Powell, warned in remarks at the Sintra conference that they, too, will keep raising borrowing costs to fight high inflation.

The U.S. inflation gauge that was issued Friday, called the personal consumption expenditures price index, is separate from the government’s better-known consumer price index. The government reported earlier this month that the CPI rose 4% in May from 12 months earlier.

The Fed prefers the PCE index because it accounts for changes in how people shop when inflation jumps — when, for example, consumers shift away from pricey national brands in favor of cheaper store brands. And rents, which are among the biggest inflation drivers but many economists think aren't well-measured, carry about half the weight in the PCE than the CPI.

Beginning with its first hike in March 2022, the Fed has lifted its benchmark interest rate to about 5.1%, its highest level in 16 years, before forgoing a hike at its most recent meeting earlier this month.

The economy has shown surprising resilience despite the Fed’s rate hikes, defying long-standing forecasts of a recession. A measure of the economy’s growth in the first three months of the year was sharply upgraded Thursday to a solid annual pace of 2%, from a previous estimate of 1.3%.

Still, the economy’s durability could prove a mixed blessing. The Fed is raising rates to try to cool borrowing and spending by businesses and consumers. It hopes employers will then reduce their demand for workers, which, in turn, could slow wage increases and inflation pressures.

Yet if the economy continues to expand at a solid pace, the Fed would likely feel compelled to send rates even higher to achieve its goal of bringing inflation back down to 2%.