By Gabriella Borter

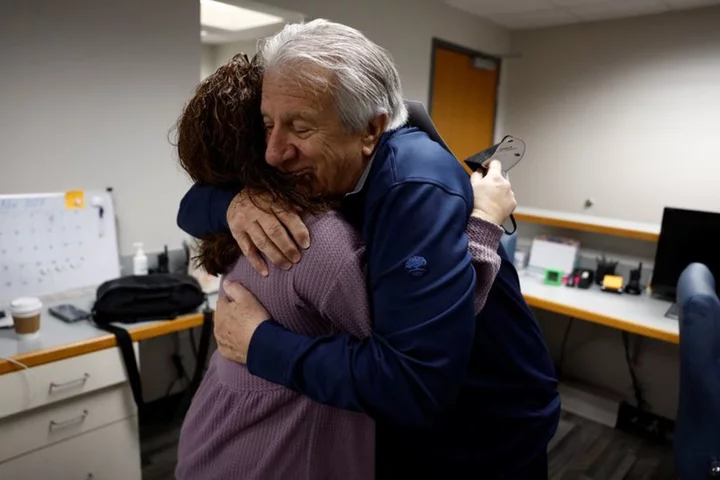

ALBUQUERQUE, New Mexico The day Alan Braid opened his abortion clinic for business in Albuquerque, New Mexico, last August, he looked out at a waiting room full of patients fresh off trips from Texas, some with suitcases in tow.

Several months later, Dr. Braid's daughter Andrea Gallegos drew a similar crowd to the opening of their abortion clinic in Carbondale, Illinois, with patients arriving from far-flung states to end pregnancies.

The father-daughter duo had their lives disrupted when on June 24, 2022, a year ago this week, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and stripped away a nationwide right to abortion.

After the landmark ruling, 14 states banned most abortions. Dozens of clinics closed, forcing patients to travel thousands of miles to end pregnancies. These included clinics of Braid and Gallegos in San Antonio, Texas, and Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Braid, an abortion provider since 1972, and Gallegos, manager of their clinics, decided to uproot their families in Texas to open the clinics in New Mexico and Illinois, two states where abortion remains legal.

After Roe, Reuters documented their days spent in airports and weeks living out of suitcases.

Braid, 78, had fewer afternoons watching his grandchildren play with the golf simulator in his garage, and Gallegos, 40, missed taking her children to karate practice.

Abortion has long been a politically divisive issue in the U.S., with abortion opponents concerned about preserving life from conception and abortion rights advocates standing for a woman's bodily autonomy.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll conducted in October 2022 showed 56% of Americans support legal abortion in all or most cases.

Braid and Gallegos faced angry protesters outside their clinics, snubs from local contractors who oppose abortion and the logistical hurdles of opening businesses hundreds of miles away from their San Antonio homes.

The undertaking was one few others pursued.

Of the 27 new clinics that have opened in the past year in states with permissive abortion laws, six are operated by providers who moved from states that now ban abortion, according to data collected by Middlebury College economics professor Caitlin Myers. Two of those are Braid's.

"I don’t think I ever really thought about quitting," said Braid, who made national headlines when he defied Texas law in September 2021 by performing an abortion on a patient who was past six weeks pregnant.

"My motivation," he said, "is to provide a safe place for women to come who have made the decision to terminate their pregnancy."

DAUGHTER MOVING TO ILLINOIS

Gallegos was in high school when she stumbled upon an anti-abortion website that called her dad a murderer and listed his work address.

She had grown up in awe of her father's obstetrics-gynecology work. Becoming aware of the risk he faced in choosing to provide abortions suddenly made that work seem even more important.

In 2020, she became executive administrator of Braid's abortion clinics in San Antonio and Tulsa. She didn't want the staff to know she was his daughter, but Braid could not wait to tell everyone.

"It was great having her aboard," Braid said. "She’s very passionate."

The last year has put Gallegos' passion to the test.

In November, she launched the abortion clinic in Illinois, one of the states that has become a destination for people seeking to end pregnancies because of its protective laws and central location.

In Illinois, abortion is legal until a fetus can survive outside the womb, usually around 24 weeks of pregnancy, and later if the patient's health is endangered.

The one-story building with a blue roof in Carbondale has drawn patients from Missouri to Florida, Gallegos said. Braid, her father, is one of the doctors who work there.

She flies almost weekly to the new location, relying on video calls to see her husband and children, ages 4, 6 and 18, back in San Antonio.

On one trip Reuters joined, she sat for hours on a grounded plane in Oklahoma City as a tornado and hailstorm raged outside. The flight made it to St. Louis in the middle of the night, where she grabbed ramen from the hotel lobby and slept a few hours before driving to work in Carbondale the next morning.

In July, her family will leave Texas and move to Illinois. The transition is bittersweet. Seeing her old home packed up and having family and friends over for one last gathering made Gallegos emotional, but she feels the excitement building for the next chapter.

“I know now more than ever that this is exactly where I was supposed to be,” Gallegos said.

FATHER MOVES TO NEW MEXICO

In August, Braid handed an abortion pill to Caitlyn, a 19-year-old mother of two from Houston who had traveled to his Albuquerque clinic. The sound of drilling from ongoing renovations echoed as he gently explained how the pill would work.

Caitlyn, a restaurant hostess, teared up recalling how scared she had been on her flight to New Mexico, her first time leaving Texas. She had not told her mother where she was going because her mother opposed abortion. But Caitlyn was determined to not have a third child.

“It would just be way too much,” she said.

It was the clinic's first week. An Oklahoma college student, five weeks pregnant, had driven nine hours overnight to make her appointment. A 32-year-old nurse from New Orleans was a day late because of flight delays.

To open the clinic, Braid and his staff had to obtain new medical licenses and move their families. During the building renovation, some contractors who opposed abortion refused to work with them, Braid said.

Anti-abortion activists resented that New Mexico had become a refuge for those seeking to end pregnancies. The state allows abortion throughout pregnancy.

"It’s definitely not what you’d want your state to be known for," said George Sieber, 61, as he protested outside a nearby abortion clinic.

Like his daughter, Braid spent months commuting from San Antonio for work. But he, too, ultimately decided to leave Texas.

In May, Braid and his wife moved into their home in New Mexico. He plans to set up his golf simulator in the garage, to be ready for his grandchildren when they visit.

(Reporting by Gabriella Borter; Additional reporting by Evelyn Hockstein; Editing by Colleen Jenkins and Howard Goller)