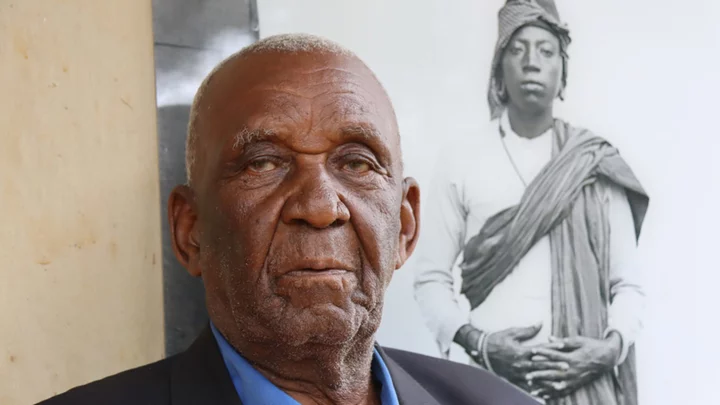

To hear 11-year-old De'Evan McFall tell it, he was going all the way to the NFL or NBA.

"He was so good that everybody knew about him in the league. The other teams knew about him. Other teams would try to recruit him," recalled Byron Sanders, who coached De'Evan's Dallas-area youth football team, the DeSoto Colts.

The lanky fifth-grader was just beginning to learn how to channel his boisterous energy and natural athleticism into becoming a star player in the league, Sanders said.

And De'Evan could have been far more than a youth league legend if he had the chance, the coach believes.

But on January 15, De'Evan was shot and killed by a stray bullet fired by a teenage girl who was fighting another girl, Dallas police said. The teen who fired the gun had been fighting De'Evan's sister, according to De'Evan's mother, Vashunte Settles. A 14-year-old girl has been charged with murder in the case, police said.

In just seconds, Settles became one of the hundreds of parents to lose children to gun violence this year. So far, more than 1,300 children and teens have been killed by a gun in 2023 in the US, according to the Gun Violence Archive. Firearms became the No. 1 killer of children and teens in the US in 2020.

Settles has created a GoFundMe to support her family and aid in De'Evan's funeral expenses.

De'Evan was an affectionate and outgoing child brimming with energy, which he poured into his love for rapping and passion for playing sports. After her son's death, Settles was gifted several basketballs and footballs covered in the scrawling signatures of De'Evan's fifth-grade classmates and friends who were won over by his goofy personality.

"He was just an all-around loving child," Settles said. "He could be in the worst circumstances and he's always just loving."

De'Evan had confronted several challenges alongside his family, including experiencing homelessness and an ADHD diagnosis that made focusing in school incredibly difficult, Settles said. But De'Evan faced life's hurdles with surprising determination and resourcefulness.

When he realized his mother wouldn't be able to afford the costly athletics fees required to join local teams, De'Evan communicated with the coaches -- almost all of whom waived the fees or found him a scholarship to play, his mother said.

"He played for like two to three teams and they loved him. ... They said they would pay for him because they really wanted him to play because of how good he was," Settles said.

Sanders was one of those coaches who saw De'Evan's promise.

After De'Evan joined the DeSoto Colts on a scholarship, he was eventually named team captain. His bonds with coaches and teammates strengthened as he spent hours with them on the field and outside of practice. The built-in support system seemed to offer him a "safety net" from the difficulties he faced elsewhere, the coach said.

"He was allowed to be a kid," Sanders said, recalling the hours De'Evan would spend swimming, eating or playing video games with teammates.

"The other kids looked up to him," Sanders said. "He was more vocal. He spoke his mind. He'd motivate the other kids."

Read other profiles of children who've died from gun violence

De'Evan could be relied on to play several positions -- including running back, quarterback and safety -- and could hold his own against older players, sometimes playing with the more advanced team, his coach said. But despite his natural affinity for the sport, De'Evan was driven to improve.

"All you had to do was tell him where he messed up. He took it, soaked it in and perfected it," said his godmother, Shay Govan.

And for De'Evan, his dream of playing in the NFL or NBA also included being able to provide security for his family, Govan said.

"He was going to take care of everybody, and we were all going to take a big trip. And that was just going to be our life," she said, remembering her godson's daydreams.

Gun violence is an epidemic in the US. Here are 4 things you can do today

Off the field, De'Evan's magnetic personality meant he was never at a loss for friends, and he would light up at any opportunity to rap, film TikTok dances or talk about music.

"He's a goofy person once you get to know him, but just first meeting him he's a little shy," Govan said. "But if you get to talking anything about music or dancing, that's what's going to really grab him and he's just going to burst into his real, full-blown personality."

Though De'Evan could occasionally be hot-headed, he was very quick to forgive or apologize, his mother said. Playground quarrels were easily forgotten for De'Evan, who was often eager to mend a friendship.

"Even the kids who got into it with him, they grew to love him in the end," Settles remembered. "After school, they'd be still at the school playing basketball and football. And he took up for other kids. He was just all around a great kid."

If he wasn't staying at his mother's house, De'Evan would be with Govan, bonding over music and his love of rappers NBA YoungBoy and NLE Choppa, Govan said. He insisted Govan refer to him as her own child, telling her, "I'm your son. I got two mommas," she said.

He clung to the people around him with unrelenting love and never failed to remind them he cared, his mother and godmother recalled.

"He told me every day he loved me," Settles said. "Literally every day."

Sanders believes De'Evan went out of his way to surround himself with positive people, determined to create a supporting community for himself even in difficult circumstances.

"If you gave him a poker hand, you wouldn't know that he didn't have anything in his hand. He didn't have a full house. So he was bluffing, but he made the best out of it," the coach said.

"He made the best out of his life."